Artwork

Cast

Jesus of Nazareth…………Glenn Carter

Judas Iscariot…………Jerome Pradon

Mary Magdalene…………Renee Castle

Pontius Pilate…………Fred Johanson

King Herod…………Rik Mayall

Simon Zealotes…………Tony Vincent

Caiaphas…………Frederick B. Owens

Annas…………Michael Shaeffer

Peter…………Cavin Cornwall

Apostles…………Grant Anthony, Gerard Bentall, Matthew Cross, Kevin Curtin, Paul Keating, Simon Ward Nicholson, Mykal Rand, Robert Vicencio, Paul Vickers

Priests…………Philip Cox, Peter Gallagher, Michael McCarthy

Soul Girls…………Nikki Belsher, Claire Coates, Rebecca Parker

Guards…………Mark Adams, Colin Lainchbury Brown, Gary Bryden, Mark Heenehan, Michael Small, Kevin Wainwright

Ensemble…………Irene Alano, Mark Carroll, Billy Carter, Stuart De La Mere, Perry Douglin, Lourdes Faberes, Andrea Francis, Shaun Henson, Nick Holmes, Asy’a O’Flaherty, Golda Rosheuvel

Herod Boys…………Peter Challis, Darren Charles, Ben Clare, Matthew Hudson, Fergus Logan, Carl Parris, Richard Roe, Sebastien Torkia, Brian Webster, David Wilder

Additional Performers

NOTE: Though these vocalists are not credited on the album itself, their presence in the film’s end titles indicates their contributions were no doubt included. As such, they are credited here.

Soul Girl Vocals…………Hazel Fernandes, Shena McSween, Anne Skates

Session Singers…………Mark Carewe, Dean Collinson, David Combes, Michael Dore, James Graeme, Kate Graham, Emma Kershaw, Louise Marshall, Samantha Shaw, Zoe Tyler, Henrik Wager, Mick Wilson

Orchestra

Guitar: Frank Dawkins, Fridrik “Frizzy” Karlsson, Paul Keogh, Alastair Marshall

Bass Guitar: Garry Cribb, Andy Pask, Steve Pearce

Piano & Keyboard: Pete Adams

Keyboards: Kennedy Aitchison, Peter Corrigan

Drums: Damian Fisher, Ralph Salmins, Ian Thomas

Percussion: Julian Poole

Orchestra Leaders: Paul Willey, Rolf Wilson

Track Listing

Overture

Heaven On Their Minds

What’s The Buzz? / Strange Thing, Mystifying

Everything’s Alright

Hosanna

Simon Zealotes / Poor Jerusalem

Pilate’s Dream

The Temple

I Don’t Know How To Love Him

The Last Supper

Gethsemane (I Only Want To Say)

King Herod’s Song

Could We Start Again, Please?

Judas’ Death

Trial Before Pilate (Including The 39 Lashes)

Superstar

Crucifixion

John Nineteen: Forty-One

Audio Production Information

Produced by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Nigel Wright

Engineered by Robin Sellars

Orchestrations by Andrew Lloyd Webber

Additional Orchestrations: David Cullen*

Music Supervised and Conducted by Simon Lee

Orchestra Contracted by Sylvia Addison

Session Singers Contracted by Anne Skates at Capital Voices

Keyboard Programming and Editing by Lee McCutcheon

Recorded at Whitfield Street Studios, London

Video/DVD available from Really Useful Films

℗ 2000 The Really Useful Group Ltd.

© 2000 The Really Useful Group Ltd.

* NOTE: Though Mr. Cullen is not credited on the album itself, his presence in the film’s end titles indicates his contributions were no doubt included. As such, he is credited here.

Historical Notes from a Fan

When last we left the history of Jesus Christ Superstar, Andrew Lloyd Webber, with the… er… wisdom and sophistication of age and experience (sure, why not), was attempting to re-brand JCS in the same light as his later works. He chose to do so with a West End revival at the newly renovated Lyceum Theatre, helmed by a director with opera experience (Gale Edwards) who aimed to approach the show with the same seriousness and depth as one would a classical work and designed by the same team (John Napier and David Hersey) who had given shows like Cats, Les Misérables, and Miss Saigon their now-classic “mega-musical” look. Despite a 1997 Olivier Award nomination for “Outstanding Musical Production,” it opened to a mixed reception from the critics and ran for a mere 16 months, closing on March 28, 1998. (A small box office boost was provided by the presence of Ramon Tikaram, an early Nineties pop singer then having a run of acting success as Ferdy in the BBC TV series This Life, who replaced Zubin Varla as Judas at the end of his contract, but evidently, it wasn’t enough to keep things humming.)

It seemed the Really Useful Theatre Company would have to make its money back on tour. Perhaps still smarting from Tikaram’s casting not having the intended effect back in London, they announced that they would be adopting a philosophy of casting “purely on ability and not on star names,” picking some leads who had understudied at the Lyceum (Lee Rhodes as Jesus, Golda Rosheuvel as Mary, Fred Johanson as Pilate) and relative newcomers (Ben Goddard as Judas). Also, maybe out of a feeling that too serious and classical an approach had been taken at the Lyceum, Edwards was teamed with a more conventional choreographer, Anthony Van Laast (frequent Webber collaborator who also worked on the UK tour of Tim Rice’s Chess at the start of the decade), and a new design team — sets by Peter J. Davison, costumes by Roger Kirk, and lighting by Mark McCullough — who were also engaged to work with her on the West End transfer of Whistle Down the Wind. This production would be designed specifically to tour, with none of the cumbersome (if eye-catching) moving elements that necessitated rebuilding in London, and it would have a current look, with most of the cast in strongly urban/military-oriented modern dress as opposed to a more-or-less traditional biblical approach.

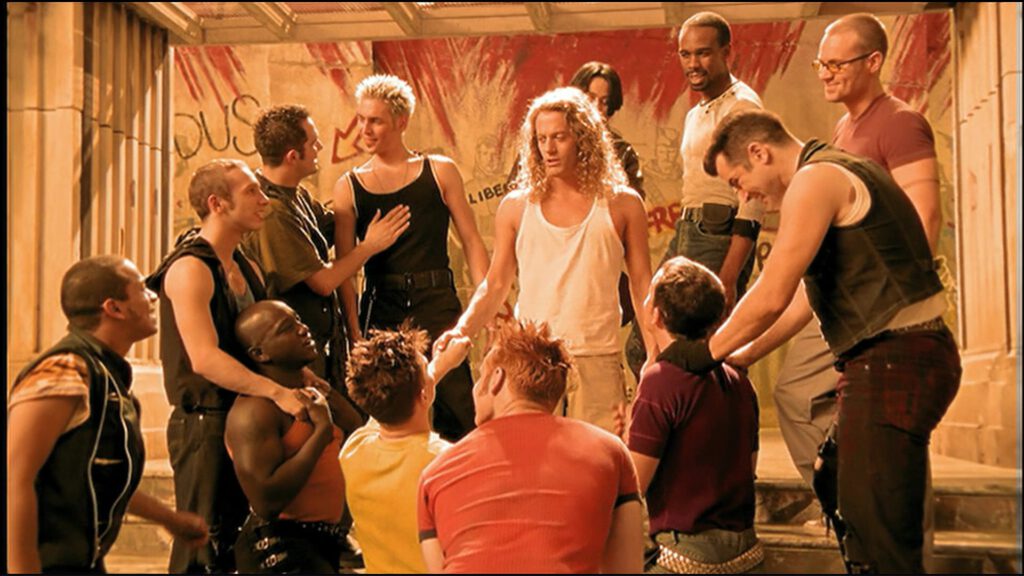

The sets, much like they did at the Lyceum, aimed for a simple, clean approach sans extraneous lighting or embellishments, but gone were the in-the-round setting, large dome, onstage seating (as well as any accompanying movement that would have involved its audience in the drama), and the like. They were replaced by something between a colonnaded courtyard and an underground train station, with a graffiti-covered back wall and a prominent horizontal architectural element in the form of a bridge or scaffolding, upon which the cast would climb up and down. (A very industrial, postmodern, pseudo-Gotham City vibe, if you will.) The moment of Jesus’ death was marked by a brilliant, blinding flash of light bulbs in the shape of a cross, echoing a similar flash upon his entrance during the overture.

The costumes were a mixed bag indeed, seeming to aim for an emphasis on politics and urban angst, with Jesus and the apostles ripped from Rent (many a waspish tongue pointed the finger of resemblance sharply at the aesthetic of that show’s gay characters), Roman guards in riot gear resembling an army of Darth Vaders with nightsticks instead of lightsabers (who participated in a slow-motion “police brutality” ballet with Jesus during “Could We Start Again Please?”), priests that stepped out of The Matrix, a Pilate in Nazi regalia, a Herod (with showgirls and chorus boys in tow) on loan from a flash-and-trash third-rate Vegas floor show back in the Thirties or Forties, a Temple full of ethnic stereotypes and a mish-mosh of dime-store criminals, a creepy Addams Family-reminiscent “lynch mob” in Goth attire that popped up only in the show’s darker moments (as when they restrained an anguished Jesus with ropes and seemingly drew blood by slapping his flesh during the “39 lashes”), and “soul girls” who cavorted in kinky rubber outfits as Jesus dragged his cross to its destination.

(Time for this reviewer’s opinionated two cents: one wonders if it ever occurred to the creative team, on the road to a rather bland soup spiced up by interesting concepts pointing in opposite directions, that the solution to a pack of conflicting ideas is not to throw them all at the wall at once; one must look for a pattern to present itself and follow it. If no pattern emerges from the fray, it’s a sign to start over. In any event…)

Plus or minus the occasional removal of darker elements for greater commercial appeal as needed, this production successfully toured the UK and Europe twice, the U.S. once (its producers at McCoy Rigby Entertainment and the Nederlander Organization, in a post-9/11 world, reportedly called for a “more joyful” experience, arguing “what we can’t do is have a bunch of guards on stage with machine guns” and that the “‘Nazis’ on stage and a lot of the blood and bumping and grinding [didn’t serve] the purpose of the show so well,” only to encounter the opposite of that experience in the form of former Skid Row frontman Sebastian Bach, who was cast in the title role on tour and dismissed early in the run for alleged divo behavior, and the untimely death of JCS veteran Carl Anderson while reprising his role as Judas), and even ran for six months on Broadway. (The tumultuous pre-production process saw the announcement and cancellation of out-of-town tryouts in Toronto, Boston, and Chicago, and the replacement of initially announced lead Jason Pebworth as Judas with supporting cast member Tony Vincent during previews.)

But before the production was to reach Broadway around Easter 2000, Andrew Lloyd Webber had a plan. Among the many divisions of his Really Useful Group was Really Useful Films, whose objective was to create film versions of his catalog. Never again, it was hoped, would he be outnumbered by Hollywood, as he had been on the 1973 film of JCS and the eventual development of Evita as a Madonna vehicle. To date, Really Useful Films had created DVD and video versions of his 50th birthday concert at the Royal Albert Hall, as well as low budget straight-to-home-viewing versions of his Cats and Joseph (which added the camera’s ability to pick up facial expressions and nuances of gesture on the actors’ part to otherwise stock renderings of the standard-issue productions of each), with a larger scale Hollywood adaptation of Phantom coming down the pike. And now, Webber had decided that this “with-it” touring rendition of JCS was the version to immortalize on video for a mass audience.

Gale Edwards was once again retained to direct the cast, with regular films division creative Nick Morris assisting with all things cinematic, with the full resources of the Pinewood Studios soundstages at their disposal. Glenn Carter, who’d started as Simon at the Lyceum before replacing Steve Balsamo as Jesus and went on to a month-long “put-in” junket in the part on the UK tour before filming began (he would play the part again on Broadway in the production that followed), essayed the title role opposite Jerome Pradon as Judas and Renee Castle as Mary. In the role of “celebrity casting to boost sales” — which had returned for film, a market more used to such decisions, in the form of John Mills in Cats and Richard Attenborough and Joan Collins in Joseph — was Rik Mayall (The Young Ones, Drop Dead Fred) as Herod. All told, the video, which wrapped production on December 14, 1999, in aiming at an (ultimately postponed) Easter release, was designed to largely resemble the UK tour, while adding a few elements intended for use on Broadway and altering a few details as needed. By this means, Webber would introduce his ideal new production to millions of living rooms in countries that had yet to experience it on stage, establishing once and for all the definitive vision of the piece.

Did it do the trick? Well, it proved by no means definitive; the video itself won an International Emmy and sold around 1.1 million copies as of the last tally (following an ambitious cinema-style international roll-out from October 2000 to December 2001), but sales don’t always account for taste, and many a bad production of JCS has succeeded despite its quality. As far as directing goes, for a show that’s supposed to run on moral ambiguity, Edwards mostly leaned into really easy, “safe” impulses when it came to defining, say, good guys vs. bad guys. Instead of exploring the characters’ motives, examining possibilities, and presenting conflicting views for consideration, she seemingly gave up on shades of gray in favor of blatant, black-and-white choices meant for the audience to just accept. The storytelling and production design are littered with the kind of offensively obvious attempts at symbolism and unsubtle “subtlety” that appeal only to pseudo-intellectual theater kids, so plain in their intentions as to almost beat one over the head with them. Annas and Caiaphas are devoutly “evil,” seemingly designed to inspire fear. With Judas, the sense of a fully three-dimensional person with any hint of inner conflict is lost, leaving a rather unlikable cad ceaselessly beating Jesus over the head with cynicism and curt remarks, their interactions an endless barrage of aggression, both overt and covert. (One wonders how we are meant to truly feel for Judas and appreciate his fall if we never see a positive, loving, friendly relationship between him and Jesus. Where other productions may not depict it explicitly, the possibility that such a friendship existed at least seems plausible in them compared to their interactions in this version.)

But we could be here forever discussing the faults of a film version that, though once touted by Webber as his ideal, is now regarded as somewhat of an “old shame,” mentioned and advertised nowhere in official marketing today. (Now the 2012 arena tour and the 2018 NBC Live presentation occupy pride of place — if you ask this reviewer, a case of “the more things change…” but your mileage may vary.) This is about the recording, so let’s talk about how it sounds.

Most people who love this video tend to love the acting more so than the singing; on the recording itself, this is laid bare, at times painfully so, without the benefit of visuals to aid or distract. Starting with the orchestrations, the superlative that comes most readily to mind is “not bad.” It would take serious strain and effort to say anything more positive than that. The tempi of some songs are inexplicably slowed to a crawl (this tends to be a hallmark of musical director Simon Lee’s work on Webber material), and for all the effort described (in the DVD’s “making of” supplement) by music producer Nigel Wright of recording a performance on tour to capture that all-important vitality (half of the fourteen credited musicians played in the pit on the UK tour) and then embellishing on that foundation in the studio, it’s surprising how often the singers overpower the instruments. As on the 1996 recording, the ability to cut loose is sorely missed; this band, for all the live vitality they hoped to capture, seems to play robotically to the metronome.

On to the vocals, such as they are. Jerome Pradon admitted in interviews to a likely inability to maintain his performance as Judas on a standard Broadway schedule, and that is readily apparent in his harsh, shrill rendition. Points to him for honesty, he is utterly out of his depth vocally, and it shows; perhaps this is sufficient explanation for his confusing choices when it comes to inflection. Fred Johanson’s Pilate suffers from similar inflection issues and is also afflicted with a case of Brian Blessed-level ham which obscures what would otherwise be an admirable take from a strong voice. Glenn Carter is never more than serviceable; his voice is strong from a theatrical perspective, but a little too sensitive in moments that call for a rock wail. Renee Castle has an overly breathy sound that suggests an unhealthy reliance on head singing, and while she deserves credit for making solid acting choices, there is such a thing as overdoing it; she chokes out the last four words of “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” as though she’s being punched in the gut between each. You know you’re in trouble when Simon Zealotes is the character to write home about — by comparison to his compatriots, Tony Vincent is a full-voiced revelation brimming with enthusiasm, and it’s easy to see why the producers picked him to take over Judas on Broadway when the first guy didn’t work out. (Frederick B. Owens’ Caiaphas is also very good, with a strong, stern, icy sound.)

As its ratings on IMDb suggest, fans either love this version or hate it. Though a bias is no doubt clear from this review, we make no judgments on that count. But we are glad to offer you any number of alternatives if this doesn’t strike your fancy.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet. Be the first one to write one.