Artwork

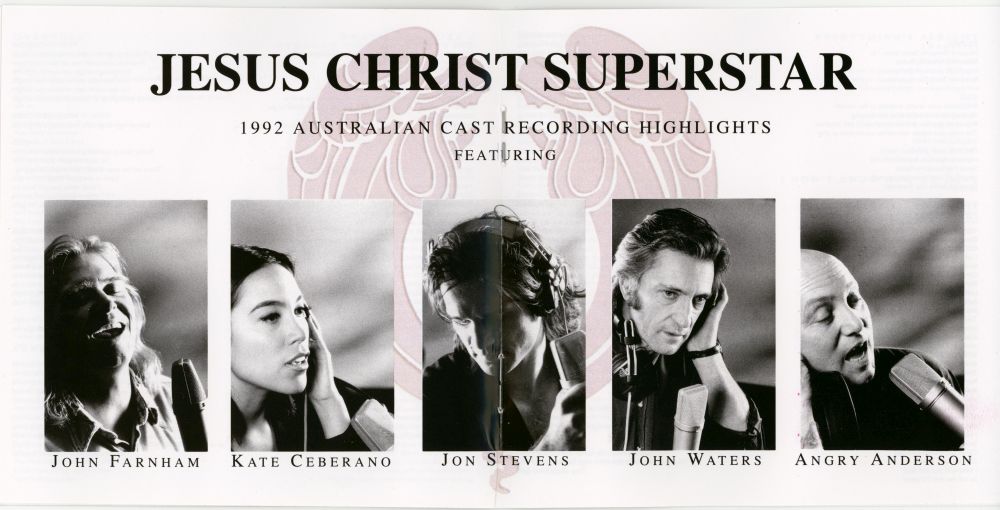

Cast

Jesus of Nazareth…………John Farnham

Judas Iscariot…………Jon Stevens

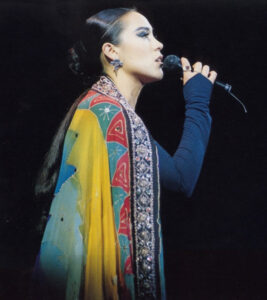

Mary Magdalene…………Kate Ceberano

Pontius Pilate…………John Waters

King Herod…………Angry Anderson

Simon Zealotes…………Russell Morris

Caiaphas…………David Gould

Orchestra

Guitars: Stuart Fraser, Willy Zygier

Bass, Keyboards, Programming: David Hirschfelder

Additional Programming (“Simon Zealotes,” “King Herod’s Song”): Gus Till

Drums: Virgil Donati

Trumpet, Valve Trombone: Russell Smith

French Horns: Russell Davis, Graeme Evans

Saxophones, Woodwinds: Tony Hicks

Harmonica, Tenor Saxophone: Steve Williams

Percussion: Geoffrey Hales

Track Listing

Overture

Heaven On Their Minds

What’s The Buzz / Strange Thing, Mystifying

Everything’s Alright

Hosannna

Simon Zealotes / Poor Jerusalem

Pilate’s Dream

The Temple

Everything’s Alright (Reprise) / I Don’t Know How To Love Him

The Last Supper

Gethsemane

King Herod’s Song

Trial Before Pilate (Including The Thirty-Nine Lashes)

Superstar

John 19:41

Historical Notes from a Fan

There is a presence in popular culture, a looming phantom […] I have seen it in the dusty beams of movie projector lights; I have spied its dusty fingerprints all over television screens and radios. It is particularly fond of advertisements, but will turn up just about anywhere. I am talking about Nostalgia, which coats popular culture with a light […] film of dust. You know that Coca-Cola’s sales are lagging when they are turning out these curvaceous old glass bottles. Rice Krispies come in old-fashioned packages now with Norman Rockwell-esque children spooning it up on the box. Hershey’s has jumped the bandwagon and adopted an antiquated face too, with Ye-Olde-looking paper wrapped around some of their chocolate bars. Does this new wave of oldness really grab the public eye? It is endearing, I suppose, this cozy retrospection…

— Wendy Kagan, “Nostalgia craze sends art back in time,” Left of Center (Vol. 4, No. 1), September 1, 1990

At one point or another, everybody is nostalgic for the decade in which they came of age. Every surviving member of each nostalgic decade has something to miss: music, TV shows, Saturday morning cartoons, hanging out with your friends at the skating rink or the mall, or over an egg cream at the drugstore (choose your nostalgic junket). And, on average, the big waves of nostalgia take about 15-25 years to get going.

In the Nineties, a lot of Seventies nostalgia got big. From 1988 (when it premiered after the Super Bowl) to 1993, The Wonder Years, an Emmy-winning “coming of age” family show created specifically to appeal to the baby-boomer generation with its late Sixties setting, created much the same buzz that Happy Days (on TV) and American Graffiti (on film) had created for the Fifties during their Seventies heyday. So, as you might imagine, the time was ripe for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ Superstar, and like the manifold artistic depictions of the figure at the center of its story over the past few centuries, it would return in many guises.

In Australia, this was marked by the hope that lightning would strike twice in the same place. Harry M. Miller, who had produced the original Australian run of JCS in the early Seventies while already a successful concert promoter through his Pan Pacific Productions, had gone on to much more success as a theatrical impresario with such hits as The Rocky Horror Show, and prominence in important circles as chairman of the society at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. After years of successful production, his career had been marred at its end by a scandal: in 1978, he had founded a ticketing company called Computicket which went belly-up within six months, causing Miller to reportedly collapse from stress. In 1982, he was ultimately found guilty of fraud and served ten months in prison. At that point, he accepted forced retirement gracefully, consumed with lecture tours and the grazing and breeding of Simmental cattle. But ten years on, Harry felt the siren call of show-biz and decided he wanted to rebuild and start the clock once more. As JCS had once been his good luck charm in the early Seventies, he elected to reinvent the piece in its initial form (e.g., a concert event, ostensibly to celebrate the 20th anniversary of its Australian opening), pack it with stars, and rake in the big bucks.

Enough people believed in his idea for fellow entrepreneurs Garry Van Egmond and International Management Group to sign on as producers. The move to pack it with stars paid off: the cast was a veritable who’s who of Australian entertainment, most notably including John Farnham as Jesus, Jon Stevens as Judas, Kate Ceberano as Mary Magdalene, and Angry Anderson as King Herod. Though a noteworthy legit director was engaged, Richard Wherrett, Miller’s new production leaned far in the opposite direction from serious theater and more toward concert/arena fare: costuming included a complete lack of sandals, the rock guitar solo introducing the show was played by a guitarist on a spotlighted and elevated platform, and there were enough atmospheric laser effects to fill a venue by themselves, including red flashes to represent each lash in the trial sequence, pinpoints to pick out the crucifixion wounds in the show’s penultimate sequence, and a show-closing expanding cone of green centered on Jesus’ crucified corpse that shone through the mist to eventually envelop the whole audience. (Indeed, the show was so thin on actually conveying the plot that — it is gleefully reported by proud atheist and equally proud JCS fan Mark Jabara — a note had to be included at the back of the program for the benefit of largely secular Australia explaining who Jesus was and gleaning a few details about his life and the events of the show’s story from prominent theologians. As an Australian poster to the JCS Zone forum put it, “Most Aussies know Jesus as the bloke whose birthday it is at Xmas and we get a day off for that so hats off to him. He’s also the bloke that got crucified at Easter and we get four days off for that. Thanks again JC.”)

Luckily for Miller, lightning did strike twice in the same place this time around. Over 84 nights, one million people flocked to the show, producing grosses of $40 million (AUD) in just 16 weeks. (Indeed, the day the box office opened, tickets reportedly sold at a rate of 400 per minute, with extra performances being added wherever possible.) Though certain snobbish critics didn’t care for the show as a theatrical endeavor, audiences ate it up as an evening of contemporary rock and pop performed by an all-star ensemble, establishing a new form of much-imitated (but rarely, if ever, to the same level of success) mass entertainment in Australia. The cast recording we review here was no slouch either; owing partly to the star names and partly to the show’s renewed popularity, it went on to become the highest-selling album in Australia for 1992, winning an award recognizing this honor at the 1993 ARIA Awards (where it was also nominated for Best Original Soundtrack or Cast/Show Album). Debuting at #1 in Australia, it remained at #1 for 10 weeks (and ultimately hit #1 on the end of year charts), and went platinum four times.

Intriguing footnote: this highlights edition recorded in the studio was supposed to be followed by a live rendering of the full score, but was blocked by trade union issues. A live recording of “Could We Start Again Please?” intended for the full live album appeared as the B-side of Kate Ceberano’s “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” single, with only a handshake agreement between the cast and the record label to use this recording. A royalty dispute ensued, and the live CD was shelved as a result. Thus, barring the pro-shot video of the show’s run in Sydney that has since leaked (and, as of this writing, is available in full on YouTube), all we have as an official record of the proceedings is this album.

Almost 30 years on (as of this writing), it’s interesting to look back at this recording. Among other things, it boasts updated arrangements by David Hirschfelder, John Farnham’s musical director (and the show’s assistant musical director), which introduce some changes that might have been considered radical at the time (a newsgroup poster in the era categorized the show as an “even more rock version”) to the score. Today, one can hear all too easily the then-contemporary, very “Top 40” influences present in Hirschfelder’s take on the score (the opening of “Everything’s Alright” calls to mind “I Just Can’t Wait to Be King” from Disney’s classic Lion King, “Simon Zealotes” veers uneasily from C+C Music Factory to Right Said Fred, “Pilate’s Dream” resembles Enigma’s “Sadness,” “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” seems a softer take on Luther Vandross’ “Power of Love,” “Superstar” stops just short of EMF’s “Unbelievable”), but there are some interesting changes that still resonate, like the imaginative use of percussion and sitar in “The Temple,” which truly conjures up the desired “sleazy bazaar” effect, and the “arena rock”/heavy metal rendition of “King Herod’s Song,” which is stronger dramatically and fits better into the score — and this rendition in particular — than the traditional raucous, blackly comic, British music hall song-and-dance arrangement. (I especially like the chorus of “Oi”s toward the end when Herod gets fed up with Jesus’ non-compliance.)

However, the tracks that have aged best, at least for this reviewer, are those that are relatively untouched by updating. Though that is not to say I can’t take re-envisioning, it’s easy to see why it is reported that Andrew Lloyd Webber, though he approved these arrangements for use in the production, was not a super fan of the liberties taken (he is notorious for having very specific ideas about how the score should sound, about which more will be heard as this Discography slogs through the Nineties and early Aughts). It should be noted, however, that Webber’s distaste was not such that it extended to any rumored legal trouble between Webber and the producers, a falsity that once circulated through a fan community who found it all too easy to believe that Webber would stamp out any updates to JCS that didn’t originate from him and was erroneously repeated as fact by veteran JCS performer Danny Zolli in his JCS Zone interview.

As far as performances go, John Farnham often ranks among people’s list of favorite Jesi (plural of Jesus) around the JCS Zone forum, and it’s not hard to see why. He doesn’t do the traditional screams or high notes on tracks like “The Temple” or “Gethsemane,” but he still succeeds at making the role his own, and doing it in his style rather than following a well-worn path. In the case of “Gethsemane” in particular, Farnham shows that a G5 doesn’t necessarily “make” the song, and a great singer can pull it off without one; ultimately, the song is done more justice by his not attempting to strain for one, and his range is still pretty high anyway. Kate Ceberano is gorgeous and sings well, but this reviewer could have done without some of her attempts at acting (the whispered “I love him, but he scares me” at the end of “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” in particular is a bit precious). Jon Stevens, if he errs a little more on the side of caution with his Judas (sounding too often like an Aussie Carl Anderson), is captivating. John Waters, playing Pilate, is fine but not particularly amazing.

The only low point, ironically enough given the fact that the arrangement works well, is Angry Anderson’s Herod. The performer comes across as a foul, untalented bore, which, while it may be appropriate for the character of Herod, does not lend itself well to repeated listening. And every singer on the album suffers from its over-the-top (over)production, including lots of reverb of varying intensity adding artificial power and enhancement to vocals that (mostly) don’t need it (only Angry Anderson seems to have the kind of vocal shortcomings that would benefit).

All in all: the music of the score holds up today. Most of what you hear on this album (the overly processed vocals and some of the more dated re-arrangements, for example) does not. But this album still ranks as a worthy, indeed necessary, addition to any JCS fan’s collection.

Reviews

Excellent

Loved the show. A good friend of mine Gary Baade gave a great support role!

1992 was the BEST performance

Absolutely loved the 92 performance. Farnham, Stevens and Ceberano, Waters and Angry! What a cast! It had feeling, it moved you. Makes you remember the words and how it made you feel.

Outstanding Performances!!!!

Outstanding performances!!!! I was “Especially, Absolutely, blown away by Jon Stevens performances playing “Judas” All I can say in “WOW”!!!! Kate Cerbano was also amazing as “Mary Madeline” John Farnham was also great as Jesus of course! …but for me Jon Stevens stole the show!

Essentially great overall

This cast of JCS is actually pretty good. The pop and rock feel is just combined together in this production and it’s output makes its debut in Superstar.

John Farnham at his best

Fantastic casting