Artwork

Cast

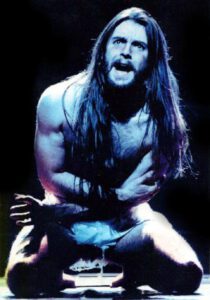

Jesus of Nazareth…………Steve Balsamo

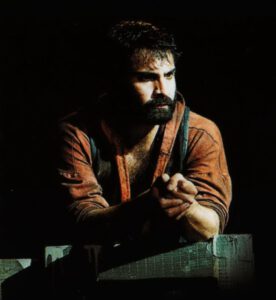

Judas Iscariot…………Zubin Varla

Mary Magdalene…………Joanna Ampil

Pontius Pilate…………David Burt

King Herod…………Alice Cooper

Simon Zealotes…………Glenn Carter

Caiaphas…………Peter Gallagher

Annas…………Martin Callaghan

Peter…………Jonathan Hart

Orchestra

Guitar: Fridrik Karlsson

Guitar: Paul Keogh

Bass Guitar: Steve Pearce

Piano: Pete Adams

Keyboards: Andy Lynwood

Drums: Ralph Salmins

Percussion: Keith Fairbairn

Track Listing

Act 1:

Overture

Heaven On Their Minds

What’s The Buzz / Strange Thing, Mystifying

Everything’s Alright

This Jesus Must Die

Hosanna

Simon Zealotes / Poor Jerusalem

Pilate’s Dream

The Temple

Everything’s Alright (Reprise)

I Don’t Know How To Love Him

Damned For All Time / Blood Money

Act 2:

The Last Supper

Gethsemane (I Only Want To Say)

The Arrest

Peter’s Denial

Pilate And Christ

King Herod’s Song

Could We Start Again, Please?

Judas’ Death

Trial Before Pilate (Including The 39 Lashes)

Superstar

Crucifixion

John 19:41

Audio Production Information

Produced by Andrew Lloyd Webber, Nigel Wright, Tim Rice

Engineer: Robin Sellars

Assistant Engineers: Jake Davies, Lorraine Francis, Ben Georgiades, Dave Huron, Gustavo Moratorio, Jason Westbrook, Toby Wood

Mastered by Barry Woodward at Townhouse Studios

Album Co-ordination: John Waller

Orchestrations by Andrew Lloyd Webber

Musical Supervisor and Conductor: Mike Dixon

Chorus Master: Simon Lee

Music Preparation by Mark Graham for Dakota Music Service

Orchestra Contracted by Sylvia Addison for London Musicians Ltd.

Choir Contracted by Anne Skates for Capital Voices

Keyboard Programming: Lee McCutcheon

Electronic Music Programming: Music Arts Technologies, Inc.

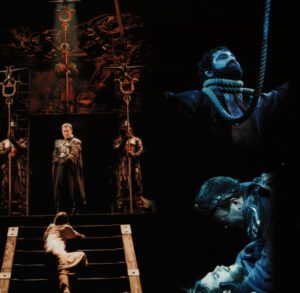

Production photographs by Michael LePoer Trench

Recorded at Whitfield Street Studios, CTS Studios, Metropolis Studios, AIR Studios (Lyndhurst Hall), Olympic Studios, London; The Enterprise Studio, L.A.

℗ 1996 The Really Useful Group Ltd.

© The Really Useful Group Ltd.

Historical Notes from a Fan

The groundswell had long been rumbling in the direction of a major revival of Jesus Christ Superstar. Successful productions toured America, Australia, and the UK to mark the twentieth anniversary; several noted alt-rock artists collaborated on separate tributes to the original album; and, perhaps most importantly, Robert Stigwood’s contractual hold on the show finally lapsed.

Though it had been, in the opinion of most observers, well represented by Stigwood since its live inception, Andrew Lloyd Webber had been less than thrilled with the results of the original Broadway production of JCS in particular and frustrated with the terms of his wide-ranging agreement with Stigwood which led to that predicament. Writing program notes for the production which spawned this recording, Webber wrote, “I shall never forget the saga of Jesus Christ Superstar on Broadway. Never — in my opinion — was so wrong a production mounted of my work. Even though this brash and vulgar interpretation was quite leniently dealt with by the critics at the time, the public saw through it. The biggest selling double album of all time ran in its first theatre incarnation a mere 20 months. Throughout its entire preview period, I was never allowed to rehearse the orchestra. Looking back 25 years later, I suppose there were pluses. Because the production was so awful, no production of Superstar in the rest of the world was the same, so I had a baptism of fire by a kaleidoscopic gaggle of directors. Most important, I resolved that night that when I got my first opportunity I would start my own production company.” In 1977, Webber did just that, founding The Really Useful Group to license and promote his shows and music around the globe, and in general taking greater control of the management of his creative works thereafter. Once he regained control of the rights, it was only a matter of time before re-branding JCS in the same light as subsequent pieces became his next big priority.

After being so impressed by her work on an Australian production of Aspects of Love that he brought it to the West End for a limited engagement following the conclusion of the Trevor Nunn original’s run, and collaborating with her on the workshop mounting of his then-new piece, Whistle Down the Wind, at his annual Sydmonton Festival, Webber began discussing the possibility of a new production of JCS with director Gale Edwards and designer John Napier (original productions of Cats, Les Misérables, Miss Saigon, and Sunset Boulevard, among others). To hear Edwards tell it in a later documentary, he had a very specific vision of what he didn’t want: “Andrew said, ‘I want a new production, and I want it redefined for the late Nineties. I don’t want a revival of a ‘rock opera’ with everyone in bell-bottom pants leaping about.’” Her program notes for the ensuing production explained what he did have in mind: “…he showed me a painting by Holbein of the dead Christ laid out on a cold slab [The Dead Christ in the Tomb, housed at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland, a painting once described by Webber as “astonishing, timeless and horrifying”]. The painting was brutal and deeply moving yet lacked any sense of sentimental romanticism… no elegantly draped arm or light-washed reclining torso, this was a raw and cruel view of death… a private viewing of a man, yet one that conjured greater thoughts. Andrew offered up the picture saying ‘This is what I think Superstar is really about.’ And so we began.”

Edwards, a veteran of opera and classical theater, discovered she had her work cut out for her when she dove into the show: “It was immediately obvious that the piece is a powerful work of theatre whose central characters, driven towards their doom by forces they cannot control, have much in common with Shakespeare’s great tragic roles. Jesus is a unique figure, aware of his destiny and the violent end awaiting him, wishing to avoid it (‘Take this cup away from me, for I don’t want to taste its poison’) but bowing to the inevitable. Although his destruction is ensured by three opponents (Caiaphas, Herod, and Pilate), all of them weak men under pressure who made the morally wrong decision for their own reasons, the central relationship of the story in the musical is that between Jesus and Judas. Investigation […] led us to the belief that both Jesus and Judas are impelled through the events of the story by a God who controls their Fate and uses them as instruments for His higher purpose. Judas becomes as much a victim of Fate as Jesus does. Both men are friends, intellectual sparring partners, and finally opponents. Both seem to instinctively understand the plight of the other but both are powerless to ease the other’s suffering. And they both suffer. Love and hate, duty and betrayal, need and blame seem to wrestle in an inevitable dance of death that neither of them can stop. […] We set out to illustrate man’s essential humanity in a production where the politics against which the action is played out — the clash between public and private responsibilities — would be of prime importance, and where the tragic human dilemma of the characters would become accessible to a modern-day audience who would hopefully recognize contemporary forces which operate in our world.”

The production design was another big discussion. Webber was not on board with a glitzy, high-tech, whiz-bang approach akin to the 1971 Broadway production (or, for that matter, most big West End musicals at the time); nor was he particularly keen on replicating the 1973 film. He wanted an “uncluttered, rough” approach; per Edwards, “decoration and embellishment were minimized wherever possible.” Perhaps this was why he chose Napier, who came without any preconceptions, not having seen the previous stage versions of the show. They agreed the order of the day was “earthy simplicity,” as Edwards put it. Napier found the story and the music “dramatic and powerful,” and searched for “a way to present it to the audience without distracting them by too stylized an approach […] to tell a superbly dramatic story in as gripping and direct a way as possible.” Costumes would not have been out of place in ancient Israel, but could as easily be seen in modern streets. Pilate’s soldiers would be cloaked in dark, metallic, threatening outfits, blending a mixture of ancient Rome and 20th-century riot police. In terms of scenic design, he proposed setting the action in the round, with a set resembling an ancient amphitheater — used for presenting plays from the ancient Greeks to the present day, such as the Olivier stage at the Royal National Theatre, and bearing an association with a life and death struggle, whether between the gladiators of old or in the bull rings of modern Spain — that spilled out into the stalls and stage boxes and incorporated onstage seating at the back facing the auditorium for three rows of the audience. It was felt this “achieved an immediacy of presentation that physically involves the audience from the moment they take their seats; an expectancy that something dramatic is about to happen; and a set that has these qualities whilst having the same timelessness as the costumes.” At the time, Edwards boasted that Napier’s “elegant, simple, raw arena” deliberately contained “only two moving elements (and even they are pretty basic!).” David Hersey, Napier’s Les Mis and Miss Saigon collaborator (who’d also worked with Webber on Evita and Starlight Express, and both Webber and Napier on Cats), was drafted to “eliminate anything extraneous in the lighting and pursue the simple, clean images that would support the storytelling.”

As embarrassed as Webber seemed to be by his early musical styling, once complaining that “the idea of a ‘rock opera’ sounds like a late 60’s time-warp,” he ultimately decided he should not change any of the music. (The only significant alteration came in previews when he felt “the orchestration of the final scene […] had to be stripped to its bare bones.”) But this created new problems for their “human” approach. To quote Edwards, “…we came up against the question of style. Traditionally a strong dance show, Superstar is a rich and brilliant musical score — and much of it is rock ‘n’ roll! Would the kind of epic storytelling with a psychological investigation of the text, of characters, of relationships work with numbers that are irresistible rock songs?” Ultimately, Edwards decided, “I needed a choreographer for whom the word ‘dance’ would be a ‘flexible’ term…” and she found one in Aletta Collins. “A wonderful colleague and collaborator,” Collins helped Edwards “create a style of playing that would feel physical and athletic, but where dance steps would be at a minimum, and the drama would dictate the onstage action.”

A period of rigorous casting followed. By Webber’s count, they auditioned over 1,200 actors; Edwards recalled that the company (ultimately of 36) was discovered in “what felt like endless auditions which took us beyond Britain to Europe and occupied (off and on) nearly a year of our lives.” People who were used to the style of the traditional JCS evidently wouldn’t cut the mustard in a production that “concentrate[d] very much on the performers as storytellers.” But come summer 1996, a cast had been announced, as well as a venue: the show would be led by newcomer Steve Balsamo in the title role, opposite Zubin Varla (Cyrano de Bergerac and Julius Caesar, both in the West End) as Judas, Joanna Ampil (London, Australia, and “international recording” of Miss Saigon) as Mary Magdalene, and David Burt (Cats, Chess, Les Mis) as Pilate, and would reopen the long-closed Lyceum Theatre in London that fall.

Following its November 19 opening, the show was met with mixed — and contradictory — reviews. Everybody loved that the Lyceum had been handsomely restored to full theatrical life for the first time in fifty years, but nobody could agree on the production’s best elements, except to opine almost as one that the score held up well for being the most of its time of Webber’s oeuvre. Otherwise, on average…

- None of the critics were particularly thrilled with Tim Rice’s lyrics (some things never change); rumors of a falling-out between him and Webber brewed as he opted to skip the opening night.

- There was a sharp divide on Napier’s designs — the majority loved the arena setting, but outliers called it “cumbersome,” “hideous,” dismissed it as little more than “pouring rubble on the stage and placing planks across the proscenium arch,” and observed how pointless setting the show in the round was when the blocking rarely favored the onstage audience’s view.

- There were strong reviews for all of the leads, but with frequent reservations: “singing [was] not [Zubin Varla’s] principal forte”; Balsamo “seemed a little weak in the part to start with,” “lack[ed] charisma,” “usually either under react[ed] or over react[ed], but never […] the right balance,” “[did] a lot of wandering around the stage swishing his long hair around and only really [came] into his own […] in the Gethsemane scene,” and “his authority [was] muted”; Ampil was “rather reserved.”

- The piece was widely regarded as too fast-paced compared to previous productions, with one critic feeling “the whole thing would be better without an interval.”

- Approaching JCS with the same seriousness and depth as one would a classical work seemed to expose the show’s flaws to increased scrutiny. Reviewer Sue Krisman opined that Balsamo came across as “cornered into having to play Jesus as a worn-out, exhausted shell at the end of his tether like a moany old woman who is tired out after too long a day at the sales.” Steve Taylor added: “A very large cast are very earnest in what they do but in the end, you don’t care much about any of them, the piece doesn’t allow for much character development.”

Ultimately, none of these reservations kept the production from an Olivier Award nomination for Best Musical Revival, though maybe they did keep it from actually winning. (Small wonder that Edwards’ program note almost smacks of defensiveness: “There are many ways of interpreting Jesus Christ Superstar on stage (as there are with any major classical work — and Superstar is a major classic!). This is our version.”) The production itself continued through cast changes and ultimately closed in March 1998, swiftly followed by a UK/European tour with the same director and a new creative team (about which more to follow in the next Discography entry).

In spring 1997, the cast recording for this production was first released. Its American issue was limited to a highlights version, the full double-disc set being held back to coincide with the Broadway revival based on the subsequent tour, which ultimately opened in 2000. Though there are some minor differences (some of the songs fade out on record as opposed to their clear-cut endings on stage, and the decision as to which gets that treatment is rather arbitrary; some of these endings work to dramatic effect, but for the most part, one longs for the older choices), this is essentially that rendition preserved for posterity.

Unusually for a recording seemingly tied to a specific production, though most of the stage cast was present (albeit with some supporting roles swapped around; Jonathan Hart, normally merely an apostle, essayed Peter on the CD), shock rocker Alice Cooper guest-starred as Herod. Per a radio interview at the time, Tim Rice asked him to step in when the stage performer’s presence didn’t translate well to records. Cooper reportedly took his cues from Victor Spinetti’s performance on the 20th-anniversary recording, and turns in an understated but decidedly appropriate portrayal, fresh and delightful by comparison to his apparent inspiration’s approach, though a little more show tunes than one would expect.

Indeed, the whole affair smacks of “musical theater performers playing at rockers for the day,” as though they were opera students who wanted to prove they could hold their own with the likes of Ian Gillan. As a later Amazon reviewer put it, “Imagine you thought you were downloading Led Zeppelin’s greatest hits and instead you get The Jonas Brothers covering Led Zeppelin’s greatest hits.” Don’t get me wrong, the performances are passionate and deeply felt — especially from Balsamo, who displays a pure, powerful voice though his portrayal comes across as a little wimpy and lacking in maturity and depth, and Varla, whose raspy, emotional voice makes up for dodgy high notes with passion — but they’re too self-conscious to “rock out,” unable to shake the pitch-perfect enunciation of their dramatic training. (Joanna Ampil in particular suffers from this trait, with crisp, impeccable diction at the cost of emotion and nuance, more suited to exhorting the value of a spoonful of sugar before medicine than the “tart with the heart” she’s meant to play.) The supporting performances, including David Burt’s commanding, well-acted Pilate, Peter Gallagher’s intimidating, sinister Caiaphas, and Glenn Carter’s competent Simon, fare better, but not by much.

The audio production is similarly clinical, with an over-produced sound that relies far too heavily on compression and artificial reverb for the drums and vocals. Further, the new orchestrations and slight lyric changes are tolerable, but among the many drawbacks of this recording. The soul and classic rock character of the original album — the dirty-sounding Fender Precision bass, the completely dry drums, and the twangy naturally distorted electric guitars — is nowhere present in this rendition. (In fact, the approach to the music is so lazy that I’d swear they lifted the slap bass take on the “thirty-nine lashes” segment of the overture, barring some overdubs, directly from the 20th anniversary London cast recording. Compare the relevant sections of both, and tell me if you agree.) A version of this same CD that was remastered at Abbey Road Studios for a 2005 re-release offered little significant improvement, to my listening.

Is it an essential JCS recording? That’s in the eye (ear?) of the beholder. But it’s rare to hear the show’s entire score (mostly) well-sung with a full complement of musicians, and it’d work well as an introduction to JCS for more of an average musical theater fan. Also, if you’re a fan of the original who wonders why new productions look — and sound — as they do, this is an important benchmark of where that all began.

Reviews

My favorite so far

Found the concept cast feeling just a little bit outdated while the Arena was too rock and roll for me. This one hits a great middle ground and feels current.