Artwork

Recording Information

Classification: Original Australian Cast

Year of release: 1972

Language: English

Type: Stage cast

Cast

NOTE: Only leads actually featured on the recording are credited. Further casting details follow in the historical notes below. Additionally, as with the 1971 Broadway cast recording, credits for ensemble vocals merely reflect the liner notes’ report of who was in the cast at the time of recording.

Jesus of Nazareth…………Trevor White

Judas Iscariot…………Jon English

Mary Magdalene…………Michele Fawdon

Pontius Pilate…………Robin Ramsay

Simon Zealotes…………Stevie Wright

Caiaphas…………Peter North

Annas…………John Paul Young

Peter…………Rory O’Donoghue

The Chorus…………Peter Bergen, Creenagh Bradstock, Stephen Campbell, Michael Caton, Helen Cornish, Jennie Cullen, Denni, Joseph Dicker, Tom Dysart, Beverly Evans, Margaret Figucio, Robyn Fisher, Geoff Gilmour, Margaret Goldie, Nick Hill, Philip Hobbins, Gary Hoffman, Frank Howson, Shauna Jensen, Paul Johnstone, Merryn Joseph, George Kent, Peter Kirby, Nicholas Lush, Peter Maloney, Natalie Mosco, Sharon Murphy, Bjarne Ohlin, Sue Robinson, Shayna Stewart, Bonnie Truex, Kim Whitehead

Orchestra

Guitar: Mike Wade

Bass Guitar: Bruce Worrall

Piano, Acoustic Guitar: Jamie McKinley

Organ: Michael Carlos

Drums: Greg Henson

Audio Production Information

Produced and Conducted by Patrick Flynn

Mixed by John Taylor

Sound Consultants: Michael Carlos, David Woodley Page

Leader: John Lyle

Conductor: Chris Nicolls

Track Listing

Side 1:

Heaven On Their Minds

Everything’s Alright

Hosanna

Simon Zealotes

Poor Jerusalem

Pilate’s Dream

The Temple

I Don’t Know How To Love Him

Side 2:

The Last Supper

Gethsemane (I Only Want To Say)

Could We Start Again Please

Trial Before Pilate

Superstar

John 19:41

Historical Notes from a Fan

When last we left off in our history, Jesus Christ Superstar had just reached Broadway as a spectacular, flamboyant, over-the-top, eye-popping extravaganza. And neither the critics nor Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber were won over by director Tom O’Horgan’s outrageous sensory-assaulting production.

Clive Barnes wrote in the New York Times, “Nothing could convince me that any show that has sold two-and-one-half million copies of its album before the opening night is anything like all bad. But I must also confess to experiencing some disappointment when Jesus Christ Superstar opened last night. It all rather resembled one’s first sight of the Empire State Building. Not at all uninteresting, but somewhat unsurprising and of minimal artistic value.” He went on to criticize the production: “Once [O’Horgan] startled us with small things, now he startles us with big things. This time, the things got too big. For me, the real disappointment came not in the music, but the conception. There is a coyness in its contemporaneity, a sneaky pleasure in the boldness of its anachronisms, a special undefined air of smugness in its daring.” Walter Kerr later added, in the same periodical, “All that had to be done with it was to put it on a stage baldly — baldness is very much of its essence — and, after establishing a few simple traffic directions, let it sing for itself. Instead, O’Horgan has adorned it. Oh, my God, has he adorned it.” Small wonder that O’Horgan later said in one interview, “Actually, the safe way to do Jesus Christ Superstar is not to do it at all.”

In later years, writing program notes for a revival, Webber would opine, “Looking back 25 years later, I suppose there were pluses. Because the production was so awful, no production of Superstar in the rest of the world was the same, so I had a baptism of fire by a kaleidoscopic gaggle of directors.” As Rice described the same period in his autobiography, “Robert [Stigwood] had decided that he would not entrust the London show to O’Horgan, and it was extremely useful for us all to see other ways it could be done before we set up in the West End. […] Because of the general lack of confidence in the O’Horgan version, all of these were brand new productions, and none bore any resemblance to the Broadway show.” The original Australian production, produced by Oz impresario Harry M. Miller and under the directorial control of the young Jim Sharman (who would soon be helping to birth The Rocky Horror Show), as documented here, rapidly emerged as a front-runner.

Many elements came together to make the Australian production of JCS special. It drew on experience and expertise that had been developed in Sydney’s blossoming theatre scene in the late 1960s, and which first came to wider public attention with the original Sydney production of Hair. Returning from Hair on the creative end were producer Miller, director Sharman (to quote Rice re: his distinguished showbiz pedigree, “descendant of a very famous family of Australian touring boxing booth shows, who began his career as a director in the non-musical theatre, first showed his skill for handling the musical side of things when he staged a notable production of Don Giovanni for the Australian Opera, and then, moving to the contemporary, the Oz version of Hair, which was enormously well-received”), designer Brian Thomson (who had first collaborated with Sharman on the Melbourne transfer of Hair, and would go on with him to many projects, including Rocky Horror), and former Tully keyboard player Michael Carlos in the orchestra (later joined by ex-Tully bassist Ken Firth).

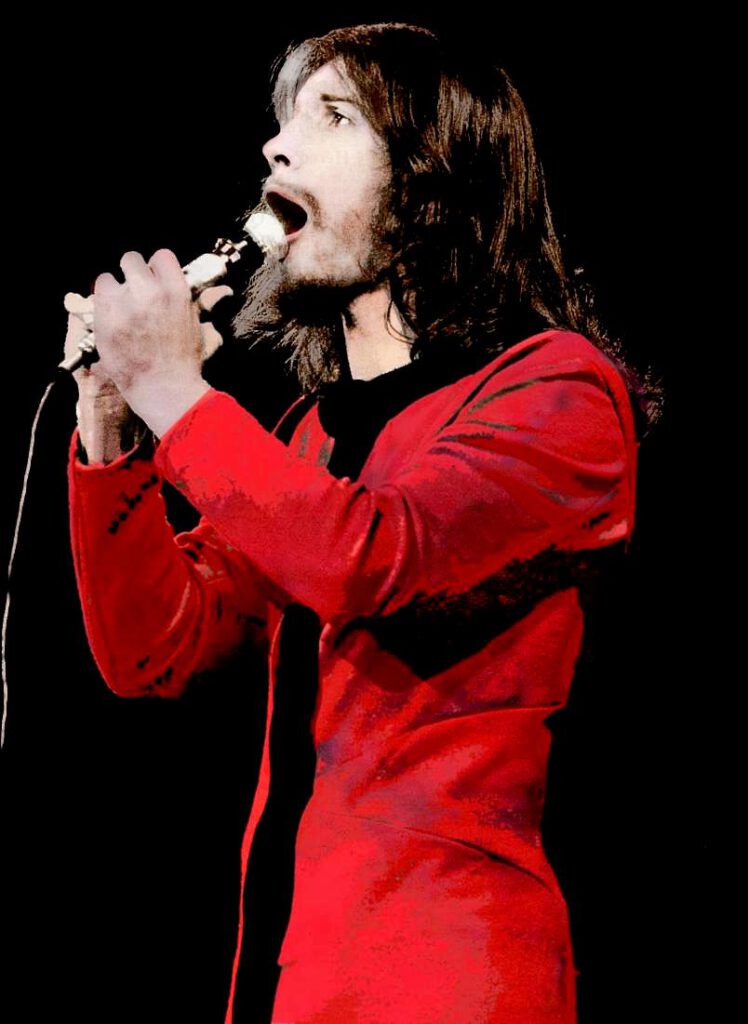

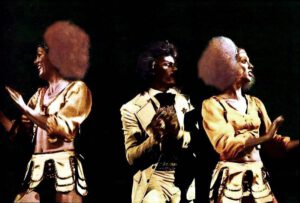

The novel demands posed by music written in the rock idiom meant that many cast members of JCS were drawn from the local pop/rock music scene — this included Trevor White (British-born singer who arrived in Australia in the mid-1960s as a vocalist with the UK band Sounds Unlimited; he would later dub Rocky’s voice in the Sharman-directed Rocky Horror Picture Show) as Jesus, Jon English (British-born former lead singer of the Sebastian Hardie Blues Band) as Judas, Stevie Wright (former lead singer of ’60s sensations The Easybeats) as Simon Zealotes, and John Paul Young (ex-Elm Tree) as Annas. However, the theater and television scene was not neglected in casting either — actress Michele Fawdon (well established on the Melbourne theatre scene and featured in numerous TV roles including Homicide) was the first to play Mary, and noted stage and TV actor Robin Ramsay (most famous for his role as nasty stock-and-station agent Charlie Cousins in the ABC’s drama serial Bellbird) played Pilate.

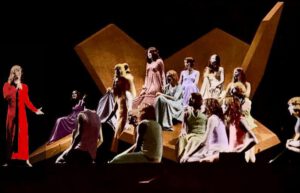

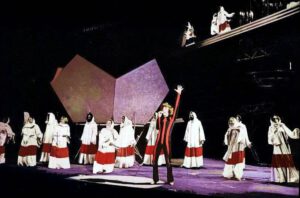

In his memoir Blood & Tinsel, Sharman speculated on what made the production work so well: “One factor was generational. In this production of Superstar, the creative team was roughly the same age as its creators, with similar strengths, weaknesses, and enthusiasms. In that sense, we captured something of the spirit of the times. I never asked Tim if he was influenced by John Lennon’s observation that The Beatles were ‘more popular than Jesus’; I simply assumed this idea informed the ironic title song. I was similarly sympathetic to the pop ethos. This version reflected a generation raised on rock music rather than Broadway show tunes.” To hear Tim Rice tell it, any approach other than O’Horgan’s would have done, but Jim’s worked for a reason, namely staging it more simply and more honestly: “Sharman replaced the tricksy, complex, tacky elements of O’Horgan’s staging by an almost Spartan space-age set. Much of the scenery, dominated by a huge dodecahedron, was clear plastic, and the costumes of no identifiable time or place. Sharman treated Superstar with considerable respect, in contrast to O’Horgan’s apparent wish to emphasize brashness, vulgarity, and shock value — not that these are not elements of the piece, but I never felt they were the most important ones. Nonetheless, Sharman’s version was highly innovative and very much of its time, very un-Broadway.”

The production premiered first in concert form (much like in the States) as an oratorio at Memorial Drive Park in Adelaide, South Australia, on March 16, 1972, as the centerpiece of the Adelaide Festival of the Arts. The show had only a simple stage, and the actors had very few props to work with. From there, the full production opened in May at the Capitol Theatre in Sydney in all its design-reduced-to-the-point-of-geometric-abstraction glory and went on to tour nationally (starting with an engagement at the Palais Theatre in Melbourne), which, with a few cast changes, ran until February 1974. This particular cast recording, though only a highlights edition, met with tremendous success off the back of the stage show, going gold in May 1973 (for sales worth $50,000), peaking at #17 on the Go-Set Albums Chart in June 1973, hitting #13 on the Kent Music Report (where it stayed for 54 weeks), and appearing in the Top 100 on the 1974 end-of-year albums chart.

Much like in the States, it was not always received warmly; the Australian JCS attracted the ire of some conservative religious groups and there were several incidents during the production’s run. Tim Rice recounts an incident on opening night: “An exciting feature of the night was an attempt at sabotage at half time, when an unknown hand (allegedly that of an affronted Christian), cut the main cable linking the conductor [Patrick Flynn, the show’s musical director and also a conductor for Opera Australia] to his orchestra via closed-circuit television [the first such video monitoring system ever used in Australian theatre]. The Twelve Apostles and Jesus came out to begin the second act unaware of this communications breakdown and patiently sat at the table waiting for the opening notes. After a few minutes, it was clear that something was wrong unless Jim Sharman had decided at the last moment to include a biting attack on slow restaurant service. Our Lord and his disciples shuffled off and the audience sat for another three-quarters of an hour before the main course was finally served. No one seemed to mind too much about the holdup, except for a few critics meeting deadlines (haha), although the Capitol Theatre did get swelteringly hot. The principal result was extra column inches in the press the next morning. The saboteur was never caught.” In an interview with Peter Thomson for the ABC’s Talking Heads, Jon English recounted two other memorable moments: “…because it was quite a controversial show, all the loonies came out in the woodwork, and once at the end of Act 1 it was, where I systematically betrayed Jesus, some nut case from the balcony… threw $6 worth of 20 cent pieces at me, and gave me five stitches over the eye […] [on another occasion s]ome idiot threw a Molotov Cocktail at the stage, but the wick came out, fortunately.”

Nonetheless, the show was a logical development from Hair in that, like Hair, it was hugely successful in its own right and also acted as a springboard that launched the careers of many of its lead players. Indeed, it can be argued that JCS was directly responsible for the launch of Australia’s entire Seventies and Eighties entertainment scene when one considers the following success stories:

- Marcia Hines (an American-born black performer who replaced Michele Fawdon as Mary in 1973, the first African-American woman to portray Mary in JCS history) went on to become a hugely popular recording artist, being crowned Queen of Pop by TV Weeks readers for three years running from 1976 and is now a judge on Australian Idol.

- Jon English became a hugely popular entertainer as both a singer and actor (JCS’ guitarist Mike Wade, formerly of Climax, and drummer Greg Henson, late of Levi Smith’s Clefs, went on to form part of English’s backing band).

- Reg Livermore (a performer formerly of Hair who replaced Joseph Dicker in the original cast as Herod and went on to truly make the role his own, transforming what was originally written as a brief comic interlude into a seven-minute song-and-dance showstopper) went on to a career-making role as Frank N. Furter in the original Australian cast of The Rocky Horror Show, which led to his becoming an iconic Australian writer, performer, and theater legend.

- Stevie Wright and Rory O’Donoghue formed a band, Black Tank, with bassist Ken Firth (who later formed the popular group The Ferrets with other musicians from JCS), and Wright went on to pursue a successful solo career as well, while O’Donoghue became a beloved Aussie TV personality as Thin Arthur on both The Aunty Jack Show and its spin-off Wollongong the Brave.

- John Paul Young became a successful solo artist and toured with various fellow JCS veterans as his backing band, The Allstars.

- Graham Russell and Russell Hitchcock, who met as chorus replacements during the production, subsequently formed the internationally successful band Air Supply.

Must be something in the water, huh? Small wonder that Tim Rice noted the strong cast and, as he puts it, “took a great liking to Jim and although I had a few reservations about some of his ideas, I was more than happy when Robert offered, and Jim accepted, the London job. Jim stated before the Sydney show even opened that he would not simply repeat himself in the West End.”

Reviews

Memorable

Wonderful cast… excellent staging… even though there were a few hiccups on open night. Favourite production. Today’s production looses the atmosphere of the story. Too much going on.

Brilliant album, wore my tape version out!

One of my all time favourite versions of JSC. I have had a few versions but remember particularly playing the tape so many times it broke. I actually saw the production in Melbourne as part of a school trip when I was around 7 or 8. I don’t recall much. We sat in the heavens (!) and probably fell asleep before the bus ride home. Amazing none-the-less.

The Best!

I saw this show in Sydney in 1972. Since then I have compared every other stage musical including more recent performances of JCS to it, and while many are very good, they cannot compare to this tour. It was the best in my lifetime.