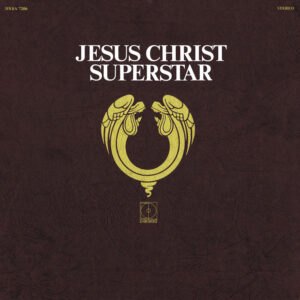

Artwork

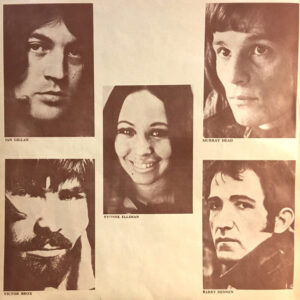

Cast

Jesus of Nazareth…………Ian Gillan

Judas Iscariot…………Murray Head

Mary Magdalene…………Yvonne Elliman

Pontius Pilate…………Barry Dennen

King Herod…………Mike D’Abo

Simon Zealotes…………John Gustafson

Caiaphas…………Victor Brox

Annas…………Brian Keith

Peter…………Paul Davis

Priest…………Paul Raven

Maid by the Fire…………Annette Brox

Other Singers (Apostles, Priests, Roman Soldiers, Merchants, Crowds, etc.)…………Pat Arnold, Tony Ashton, Peter Barnfather, Madeline Bell, Brian Bennett, Lesley Duncan, Kay Garner, Barbara Kay, Neil Lancaster, Alan O’Duffy, Tim Rice, Seafield St. George, Terry Saunders, Sue & Sunny, Andrew Lloyd Webber

On “Overture”…………Children’s choir (under the direction of Alan Doggett)

On “Superstar”…………The Trinidad Singers (under the leadership of Horace James)

Additionally…………Choir (under the leadership of Geoffrey Mitchell)

Orchestra

Primary Musicians

(Electric & Acoustic) Guitar: Henry McCullough

(Electric) Guitar: Neil Hubbard

Bass Guitar: Alan Spenner

Piano, Electric Piano, Organ, Positive Organ: Peter Robinson

Tenor Sax: Chris Mercer

Drums, Percussion: Bruce Rowland

Additional Musicians

Guitars: Clive Hicks, Chris Spedding, Louis Stewart, Steve Vaughan

Bass Guitars: Jeff Clyne, Peter Morgan, Alan Weighall

Pianos: Norman Cave, Karl Jenkins, Mick Weaver, Andrew Lloyd Webber

Organs: Mick Weaver, Andrew Lloyd Webber

Moog Synthesizers: Alan Doggett, Andrew Lloyd Webber

Drums: John Marshall

Trumpets: Harold Beckett, Les Condon, Ian Hamer, Kenny Wheeler

Bassoons: Anthony Brooke, Joseph Castaldini

Horns: James Brown, O.B.E., Jim Buck Sr., Jim Buck Jr., John Burdon, Andrew McGavin, Douglas Moore

Trombones: Keith Christie, Frank Jones, Anthony Moore

Clarinet: Ian Herbert

Flutes: Chris Taylor, Brian Warren

Strings: Strings of The City of London Ensemble (Principal: Malcolm Henderson)

Percussion: Bill LeSage

Track Listing

Act 1:

Overture

Heaven On Their Minds

What’s The Buzz / Strange Thing, Mystifying

Everything’s Alright

This Jesus Must Die

Hosanna

Simon Zealotes / Poor Jerusalem

Pilate’s Dream

The Temple

Everything’s Alright (Reprise)

I Don’t Know How To Love Him

Damned For All Time / Blood Money

Act 2:

The Last Supper

Gethsemane (I Only Want To Say)

The Arrest

Peter’s Denial

Pilate And Christ

King Herod’s Song (Try It And See)

Judas’ Death

Trial Before Pilate (Including The Thirty-Nine Lashes)

Superstar

The Crucifixion

John 19:41

50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition – Disc 3:

Ascending Chords

Damned For All Time / Blood Money – Guide Vocal

King Herod’s Song (Try It And See) – Guide Vocal

I Don’t Know How To Love Him – Tim Rice And Murray Head Vocals

I Don’t Know How To Love Him – Murray Head Vocals

This Jesus Must Die – Scat Vocals 1

What A Party

This Jesus Must Die – Scat Vocals 2

Heaven On Their Minds – Instrumental

I Don’t Know How To Love Him – Single Edit

(Too Much) Heaven On Their Minds – German Single

Strange Thing (Mystifying)

1970 Open End Interview With The Creators Of Jesus Christ Superstar – Part One*

1970 Open End Interview With The Creators Of Jesus Christ Superstar – Part Two*

John Nineteen Forty-One – Remastered 2021

* denotes that these tracks only appear on the physical release of Disc 3.

NOTE: Some track titles in streaming release may differ from those on the cover of the physical product. Sufficient explanation is provided below.

Promotional video for album’s release featuring Murray Head and The Trinidad Singers performing the song “Superstar.”

A segment from a rare promotional video recorded by Dutch news network NOS in 1971 featuring Ian Gillan performing the song “Gethsemane.”

Murray Head performing the song “Superstar” live for the first time on the British television program Frost on Saturday in 1969. (Copyright LTW/ITV)

Audio Production Information

Produced by Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber

Chief Sound Engineer: Alan M. O’Duffy

Engineers: Jeremy Gee, Anton Matthews, Martin Rushent (Advision), Stephen Vaughan

Cutting Engineer: Tony Bridge

Production Management: Don Norman

Orchestration and Musical Direction by Andrew Lloyd Webber

Principal Conductor: Alan Doggett

Moog synthesizer by kind permission (and under the direction) of Mike Vickers

The Opera was recorded at Olympic Sound Studios, Barnes; Advision Studios; Island Studios; and Spot Productions Studios on 16-track tape.

Historical Notes from a Fan

This is the very first recording of Jesus Christ Superstar, Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s second attempt at a rock opera, their first being a popular but then-less successful work called Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. With Jesus Christ Superstar, or JCS as it’s become known by fans, the two (who, at the ages of 25 and 21 respectively, were just embarking on what would become extraordinarily long and successful entertainment careers) were thrust firmly into the limelight, partly because of the innovative and beautifully crafted songs, and partly because of their often controversial handling of this sacred story.

The songs, as in all versions of JCS, recount the seven days leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus, as told from the perspective of a confused, frightened, and ultimately remorseful Judas. Rice was reportedly inspired by the Bob Dylan anthem “With God On Our Side,” from his seminal 1964 album The Times They Are A-Changin’, which features Judas in its penultimate verse. As Rice says in his autobiography: “From a very young age, I had wondered what I might have done in the situations in which Pontius Pilate and Judas Iscariot found themselves. How were they to know Jesus would be accorded divine status by millions and that they would, as a result, be condemned down the ages?”

Pitching the groundbreaking rock double album in its early days was no mean feat. Already rejected for production as a stage musical (says Lloyd Webber, “No-one was interested in doing Jesus Christ Superstar on stage when we started, so Tim Rice and I did it as a record”), record labels — Lloyd Webber and Rice’s usual home turf, as both songwriters and producers in the pop world — found it hard to get behind such an unusual piece.

Oddly, the later process of shopping the finished album around may have led, in a roundabout way, to the future involvement of the stage and film version’s producer, Robert Stigwood, with whom Rice and Lloyd Webber signed at the end of 1970. (The boys and their manager David Land, by then being approached for the film and stage rights for JCS thanks to the success of the album, signed a management deal with the Robert Stigwood Organisation because, as Tim put it, “all these people made the mistake of getting us to ring them or sending around a minion whereas Robert sent round a Cadillac and we zapped round to his place and we liked him.”) One of the first labels JCS was offered to was The Beatles’ (in)famous Apple Records. Tony Bramwell, a former Fab Four employee, elaborates in his book Magical Mystery Tours: “Many things slipped through the net in [Allen] Klein’s reign [as The Beatles’ manager], including a big stage musical that ran for years and years. The first big musical in London after Hair was Jesus Christ Superstar, the first of a dynastic series of musicals from Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. Jesus Christ Superstar was brought to Apple as a new project because Ian Gillan from Deep Purple sang on the demo and another friend, Johnny Gustafson, the bass player from Liverpool’s The Big Three, played on it. I can remember hearing it around the building at the time, with everyone singing snatches of the very catchy big theme song. But it was Robert Stigwood who ended up producing it. […] I’ve always thought that when Klein threw Peter Brown [The Beatles’ assistant and day-to-day manager following Brian Epstein’s death] out, Peter must have popped the tapes in his briefcase when he cleared his desk and took them with him to Stiggie’s place on the basis that there wasn’t a lot of interest in them at number 3 Savile Row. If he did, he was right. Peter Brown is still Andrew Lloyd Webber’s PR man in the States. If Klein had kept his eye on the ball and hadn’t been too concerned with feathering his nest, Apple could have signed Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice up and produced all their other big musicals after Superstar, like Evita, Cats…”

To get the concept album of Jesus Christ Superstar off the ground, Decca first gave Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice money to make this single and begin the album. They wanted to release the single first, which caused an uproar within the MCA board at the time. The title song “Superstar” — which kicked off the songwriting process for the album; Lloyd Webber wrote the melody down on a napkin in a restaurant on London’s Fulham Road — was recorded by Murray Head, a singer Tim knew of from his days working at EMI who had left an impression when performing with his band, The Blue Monks and Their Dirty Habits. Backed by MCA, Andrew and Tim spent a small fortune on the recording, including using a full orchestra and the backing vocals of The Trinidad Singers. The Grease Band, Joe Cocker’s backing band and one of the best rhythm sections in the world at that time, were brought in as the foundation of the ensemble. Chief engineer Alan O’Duffy, an Irish 22-year-old, committed the song to 8-track tape at the renowned Olympic Studios in Barnes, London.

With an early version of the instrumental finale “John 19:41” on the B-side, “Superstar” was released as a single in 1969 (November 21 in the UK, December 1 in the US). Martin Sullivan, the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral and former Archdeacon of London, supplied liner notes for the sleeve of the single. “There are some people who may be shocked by this record,” he wrote. “I ask them to listen to it and think again. It is a desperate cry. ‘Who are you Jesus Christ?’ is the urgent inquiry, and a very proper one at that…The singer says ‘Don’t get me wrong, I only want to know.’ He is entitled to some response.” In the UK, it was featured exclusively on David Frost’s famous TV chat show and sold as many as 3,500 copies in one day, but it met with even bigger success outside its home market, rocketing to #1 in Holland above Led Zeppelin and Elvis, and also in Belgium and Brazil, and making the Top 10 in Australia and New Zealand. In the US, it reached #14 and the single “Superstar” was #27 in Billboard’s Top 100 Songs of 1971, above hits such as George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord,” The Carpenters’ “Rainy Days and Mondays,” and “Proud Mary” by Ike and Tina Turner. The international performance of the single meant Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice had permission from MCA to go ahead with the rest of the album.

(A later single from the album would meet with similar unusual success: Yvonne Elliman’s version of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” was released in 1971 and then overtaken by a cover version from the then-unknown Helen Reddy, which peaked at #13 in the Billboard charts compared to Elliman’s #28. It remains one of the few instances in modern music where two versions of the same song have charted in the Billboard Hot 100. The song has of course gone on to be covered by many more artists in dozens of versions recorded over the years, including Shirley Bassey, Cilla Black, Bonnie Tyler, Peggy Lee, Elaine Paige, and Sinead O’Connor, who launched her 2007 album Theology with her cover.)

Casting for the album began in earnest, and not without attention from the press. Following on from their involvement in the single, The Grease Band and Alan O’Duffy were all brought back in to record the rest of the album. Head continued to sing the part of Judas and introduced Barry Dennen to play Pontius Pilate, as they shared the same management. Casting Mary Magdalene proved slightly trickier; Andrew discovered a young 19-year-old called Yvonne Elliman singing in the Pheasantry in London, but (as Tim Rice noted) her manager at the time pushed for a high upfront fee, which they agreed to pay only because she was “so good.” (More about this later.) Off the back of the single’s success, tabloid newspapers got in on the act, linking John Lennon to the project; no less noteworthy a periodical than Time magazine reported that there were rumors John had said he would only do it if Yoko Ono played Mary Magdalene. (Other unfounded rumors suggested Marianne Faithfull would appear in that role.) Ultimately, Ian Gillan from the band Deep Purple was brought in to sing in the role of Jesus.

The recording process had its interesting footnotes; for example, Paul Raven, a priest in the background of Caiaphas and Annas’ numbers, later went on to fame (and, far in the future, infamy) as Seventies glam rock star Gary Glitter. The recording process was often an exercise in experimentation as well, as this story from Ellis Nassour’s in-depth early Seventies account Rock Opera puts it: “When it came time to record the thirty-nine lashes bit for the passion sequence, Webber was not happy with the sound — it had to be harsher. Someone volunteered that the reason the sound was soft was that the studio was padded. ‘Then let’s do the bloody thing in the hall,’ Rice replied. The engineers set up microphones there, then those present were placed in various locations to provide crowd noises, and Rice, armed with a long, flat piece of board with another smaller section hinged on it, flapped away providing the lashes and doing the counting. ‘That was great,’ Webber called from the studio booth. ‘We got a good echo!’”

However, the recording process also had its trials and tribulations. According to Brian Keith, “One of the things that happened during the recording was that they ran out of money before they finished recording, so they couldn’t afford to pay us […] so they started offering a percentage of the royalties as payment. We were all skeptical about it, ’cause if it didn’t do well, we’d be out of money.” According to Rock Opera, Murray Head, a believer from the very beginning (indeed, he sometimes pitched in on background vocals, crediting his choral work to his middle name[s] “Seafield St. George,” and at one point did his best Barry Dennen impression on “this unfortunate” when Lloyd Webber and Rice discovered, to their horror, that a small part of Dennen’s vocal on “Pilate and Christ” had been erased from the master tapes), was the first to leap into the breach and opt-in on the risky profit-share plan. On the other side of the spectrum was Yvonne Elliman, who later lamented having already been paid a flat fee of £100, and thus missing out on the (eventual) huge royalty payout: “I was advised just the night before I reported to do my songs, ‘Don’t take a royalty. This record isn’t going anywhere.’ If I had taken the royalty I’d be like $100,000 richer now.” (According to the Tim Rice interview on the Special Edition DVD of the 1973 film, the authors eventually gave Yvonne a royalty “out of the kindness of our hearts.” Recent conversations with Elliman, however, suggest that “creative accounting” at a label level may be at play, as she still purports never to have received a cent.) Others who were initially skeptical changed their minds after hearing more of the work at hand. Brian Keith again: “[After hearing some of the completed album] I said right there, ‘I’ll take the percentage!’ I knew this was gonna be big as soon as I heard [it]. I still get money today from that ’cause it keeps selling.”

By the following year (some sources incorrectly date the album’s release to 1969, likely due to conflation with the initial single’s release date in the memories of older fans), the album was completed and released in October 1970. And to say that it was hugely successful is a vast understatement. The album’s popularity rocketed with thousands of plays on FM radio. It became a #1 hit on the USA Billboard album charts four months after its release. In the U.S., a Time magazine review of the album said: “What Rice and Webber have created is a modern-day passion play that may enrage the devout but ought to intrigue and perhaps inspire the agnostic young.” Meanwhile, according to Tim Rice’s autobiography, mail from all over the world flooded in, most of it thanking the young writers “for making the Gospel story clearer and more relevant.” (As Murray Head would later put it in 2012, “When Jesus Christ Superstar reached American shores the timing was perfect. They were desperate for a new way, for a new translation of the Bible, and Tim’s shrewd idea of angling it from everyman’s perspectives — through the eyes of Judas — worked a treat.”)

At this point in the review, a fan’s thoughts are almost immaterial, but this fan will endeavor to offer a few anyway, hard as it may be. After all, what can one say about the very first recording, the benchmark by which all others are measured? “It’s a pleasant listen”? One can start by saying that, no matter how many times one listens, it is impossible not to marvel at the skill that went into this album, and that Rice and Lloyd Webber produced the album themselves, long before sophistication and adjusting the show for later audiences had set in, speaks for itself. Listening to this or that performer’s portrayal, words like unusual, interesting, and virtuosic come to mind, but the one word that rends and tears anything else one would put to paper is “right.” Even though it’s only audio, everything – voices, musicians, production – is just right for what it needs to be, the perfect fit.

(Case in point for this reviewer is the apostles’ closing verse of “The Last Supper.” The lyric is, has been, and hopefully always will be “Look at all my trials and tribulations / Sinking in a gentle pool of wine…” After having no doubt imbibed their fair share throughout Jesus and Judas’ argument, the last round before they fall asleep should sound more than slightly intoxicated, if one is telling the story properly. More “careful” productions have them sound slightly unsettled, which is fine; the concept album sounds like they closed down the pub and are staggering home on the least steady of feet. Tiny details sometimes yield massive pluses, and that’s exactly what makes this album work so well.)

A Guide to Disc 3: Inside Info on the Deluxe Bonus Tracks

In September 2021, the original recording of JCS celebrated its belated 50th anniversary with a major re-release in a variety of formats: a standard 2-CD edition; a 3-CD expanded box set, with previously unheard bonus material on Disc 3, and a hardcover book with lyrics, celebrity liner notes, and a complete oral history of the album’s creation (pictured above); and 2-LP standard and deluxe editions, all of which featured a new remaster of the album undertaken by Miles Showell and Nick Davis at Abbey Road Studios.

(NOTE: Neither of the vinyl releases includes the bonus material; the deluxe LP is “deluxe” in that it replicates the original UK vinyl package, complete with psychedelic cover design, fold-out sleeve, and a 12 x 12″ print of numerous depictions of Jesus that was originally incorporated in the UK release, mixing Renaissance masters with drawings by London schoolchildren.)

The vast majority of the bonus tracks — literally all but two — are available wherever you can find the album’s “deluxe edition” on all streaming services, including Apple Music, HDTracks, Spotify (see the embedded player above), and YouTube. However, minus the fancy hardcover book (which includes written commentary by Tim Rice on each bonus track as context), the average curious listener may be befogged as to where deleted, previously unheard music may have gone on the album, to say nothing of the origin of the other tracks. Luckily, the barrel of nerds at JCS Zone has all the answers as usual, in the order they appear on the bonus disc (beware of spoilers past this point; you have been warned):

- Ascending Chords is an instrumental cue that, on its own, sounds like a generic “biblical epic” radio spot or film trailer music cue, and without expert knowledge of JCS “deep cuts,” it would be impossible to place in the final product. However, this music, unlike this particular recording of it, was not truly lost and made it into the stage version at one point. In older music scores for the show, it is labeled “End of Temple Scene” and comes directly after Jesus screams “Heal yourselves!” It can even be heard in context, minus the opening few seconds — on this version — of percussion count-in to set the rhythm, on the JAY Records studio cast and Czech live cast recordings (links are to Discography pages, not samples), both from 1995. (However, it is no longer part of the licensed version, post-Lloyd Webber takeover.)

- Skipping around a tad, Damned For All Time / Blood Money – Guide Vocal, This Jesus Must Die – Scat Vocals 1, and This Jesus Must Die – Scat Vocals 2 are all samples of the same piece of recorded music heard in both “Blood Money” and “Judas’ Death,” with loose vocalizing setting the melody for the lyrics to (eventually) follow. “Scat Vocals 2” seems to be the closest to anything near a final product, with (we assume) Victor Brox busking his way through some of Caiaphas’ “What you have done will be the saving of Israel…” verse from the death scene. All of them make for incredibly goofy listening but are nonetheless intriguing artifacts of the development process.

- King Herod’s Song (Try It And See) – Guide Vocal is exactly what it says on the label, complete with a few alternate early lyrics here and there (and a cameo from the movie’s version of the brief piano solo in the instrumental section, suggesting they didn’t just rely on the finished master when constructing the rhythm tracks for the film soundtrack [see linked Discography page], but raided the proverbial vault for alternate choices).

- I Don’t Know How To Love Him – Tim Rice And Murray Head Vocals and I Don’t Know How To Love Him – Murray Head Vocals both exist because, when Andrew and Tim were writing the album, JCS was not the sure thing we know it to be today. (Per the former’s memoir, their music publisher listened to the final cut of the album before they submitted it to MCA and cynically quipped, “…well, there’s nothing here for [long-forgotten British female pop singer], is there?”) Consequently, our young creators were attempting to stay grounded, one foot in their theatrical ambitions and the other just trying to stay afloat in the pop recording world. “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” is probably the easiest song to lift from the show out of context, considering how many times it was ultimately covered anyway, so — as can be heard here — they prepared for several possibilities, including a lyrical pronoun swap for a male vocalist. Both tracks boast some genuinely pleasant singing from Murray Head, the original “true believer” in this project. The first, however, seems to have been aimed squarely at Elvis (for whom Rice and Lloyd Webber would subsequently write a song just before his death) or someone of like variety, as Tim’s contribution amounts to speaking the first verse in a frankly ridiculous style akin to the King’s stage patter in “Are You Lonesome Tonight” or “My Way.” Save the first one for a laugh on a rough day, but both are worth hearing at least once, noteworthy in particular for the additional positive organ that was dropped from the final album version but can also be heard on the film soundtrack.

- What A Party was first written about in Rock Opera, so we always knew it existed; the only revelation was what it sounded like. If you’re unfamiliar, a quick recap: “What A Party” sets the scene for the next number, “What’s The Buzz,” placing the events to follow in the house of Simon the Leper on a Friday night in Bethany, as in the Bible, and is sung by Simon and the ensemble. Aside from a repeated chorus from the crowd, the majority of the song consists of Simon the Leper — played by the (far) above-mentioned Tony Ashton (of Ashton, Gardner, and Dyke fame) — welcoming Jesus and friends to his home, name-checking the individual apostles (presumably for the audience’s sake) and at one point slipping an in-joke into the proceedings, admonishing the future St. Thomas not to doubt the quality of the table wine. (If you listen closely, you’ll faintly hear the late Jack T. Chick “haw haw”-ing from his grave.) When it came time to finalize the piece in mixing and mastering, the label execs pressed Rice and Lloyd Webber to cut anything non-essential so they didn’t spill into a third disc and risk raising the album’s already-precarious price in the shops (a double LP was not cheap). “What A Party” got the ax. Listening to it 50 years on, in this fan’s opinion, it was an easy edit to make and decidedly the right choice; compared to the fresher sound of the rest, this very definition of filler, while still decidedly rock in its sound, is oozing with an air of “conventional musical” in purpose that JCS never needed.

- Heaven On Their Minds – Instrumental is a rudimentary run-through of the song with some jazzy “noodling” of the vocal melody at the piano and perfunctory backing from the rest of the band. A neat little exercise, but forgettable out of context.

- I Don’t Know How To Love Him – Single Edit is, again, exactly what the title claims it is — same as what’s on the album, but no final syllable of the “Everything’s Alright” reprise over the intro. Good for isolated listening and remembering when this track was all over Top 40 radio.

- (Too Much) Heaven On Their Minds – German Single was released in several markets — not just Germany — to attempt to repeat the success of “Superstar” before it. In addition to added “Soul Girls”-reminiscent background vocals, it has one unique feature best described by quoting Tim Rice’s memoir on the subject: “Having had U.S. airplay of ‘Superstar’ restricted because of the lyrical content, I very stupidly decided to rewrite parts of ‘Heaven On Their Minds’ purely for the proposed single version and Murray recorded the song all over again […] it was foolish of me to forget that the airplay that we had achieved with ‘Superstar’ was precisely because of the lyrical content, not despite it. [It was released] very half-heartedly and it sank without trace.” You can read the single version’s lyrics by clicking “More Images” under the cover at its Discogs entry. Strange Thing (Mystifying), as it was then titled, was the B-side, and amounts to an extended instrumental version of that track.

- 1970 Open-End Interview With The Creators Of Jesus Christ Superstar (Part One and Two), mercifully included only on the physical release, is a prerecorded period radio interview with Lloyd Webber and Rice — but just the answers. The questions would be supplied by disc jockeys worldwide, possessing a script to fill the gaps which is printed in the deluxe edition’s hardcover book, creating the illusion of an exclusive interview “right here in our studio!”, with select tracks from the album interspersed throughout. The easily amused may enjoy interviewing across time on an exceedingly boring day, but it’s plain to see why this was left off the streaming services.

- Last but certainly not least, John Nineteen Forty-One – Remastered 2021 is the B-side of the original “Superstar” single (and labeled as such on the physical release of the deluxe edition). Its distinguishing feature is an entirely different second half following the conclusion of the “Gethsemane” theme, a jarring and unusually jaunty primarily piano-led bit of music that sounds for all the world like a slice of late Sixties pop equivalent to the end credits of a Rocky and Bullwinkle episode. Apparently, per Rock Opera, the U.S. label thought better of including this unfitting music and lopped it off the American release. It’s amusing, reminiscent of the Overture in a couple of places, but doesn’t belong. Still, an interesting curio, to be sure.

Reviews

Fantastic! I love reading the background of this epic album. One of my all time favorites!

I live in the US and I was 7 years old when this album came out. I spent hours upon hours tucked away in my father’s den with with this album and his turntable, and later his reel-to-reel recording of JCS (he used to put all vinyl on reel-to-reel), and committed to memory every single lyric and note of this entire rock opera. I was so young and it was my first actual introduction to the story of Christ, other than from the occasional bible story (we were not church goers) told to me by a grandparent or from one of the few times we did attend a church service. And, it was relatable, even to a child, as this recording brought it all to life. I fell in love with the Jesus of JCS and his plight. I would be in tears by the end of the album – so sad for his difficult journey – but also so moved by the melodies and words of all the songs. It was always cathartic, and still is to this day, listening and participating in the experience of this recording. Each number is perfect and brilliant. Thank you so much for keeping the information out there and alive. I was able to locate the original JCS vinyl album on Ebay recently and will soon be getting a turntable so I can listen the way I did back in the early 70’s. This is a wonderful website! Many thanks.