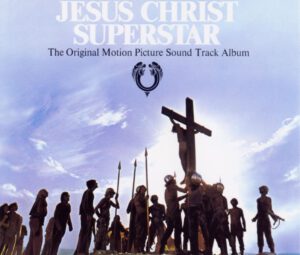

Artwork

Cast

NOTE: According to Ellis Nassour’s book on the show’s creation, Rock Opera, the ensemble vocals for the film soundtrack were pre-recorded in England by other unknown vocalists; it has also since emerged that some dubbing of actors with poor English occurred, Norman Jewison in particular recounting an instance of dubbing the old man in the “Peter’s Denial” scene on the commentary track of the Special Edition DVD. It is noteworthy perhaps for this reason that only the leads are credited in the album’s liner notes. As JCS Zone is unaware of the names of any of these people, please note that this is merely the cast as listed in the film’s credits, and may not necessarily reflect the voices heard on the album (aside, of course, from the leads). This list also does not include the leads from the French dub, who are noted in passing below.

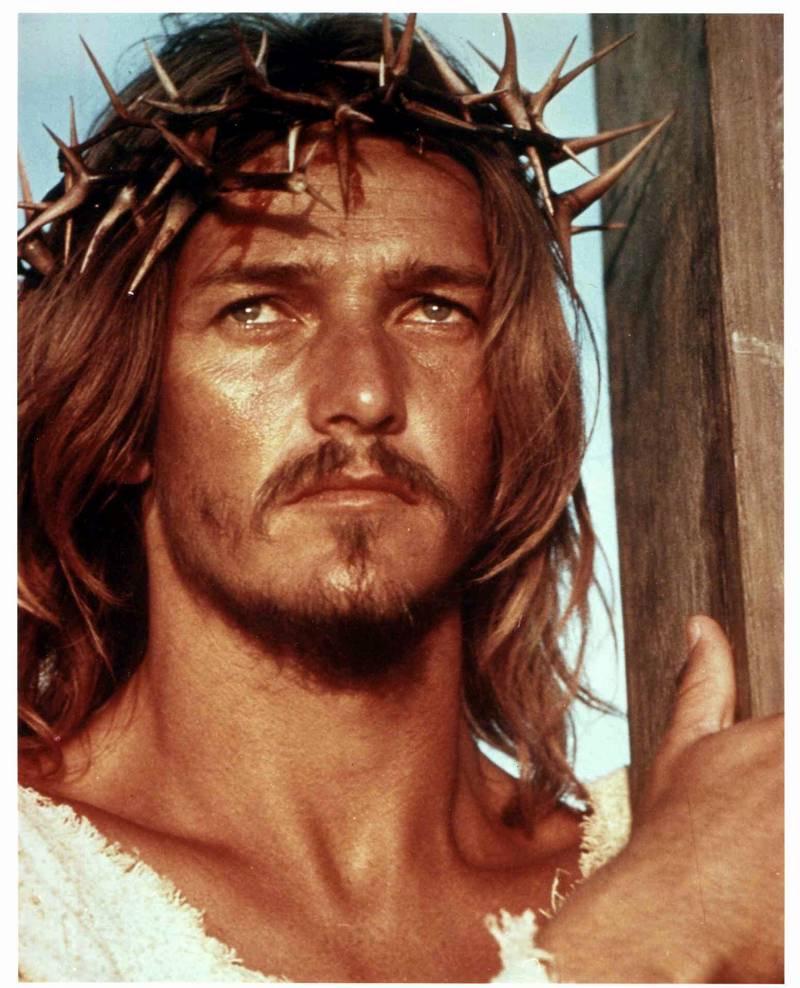

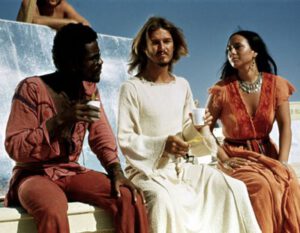

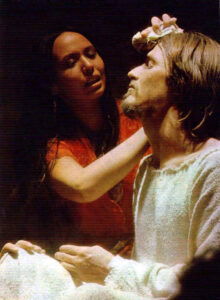

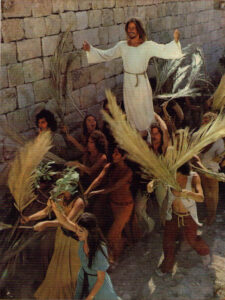

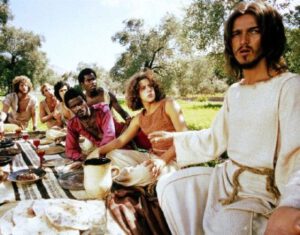

Jesus of Nazareth…………Ted Neeley

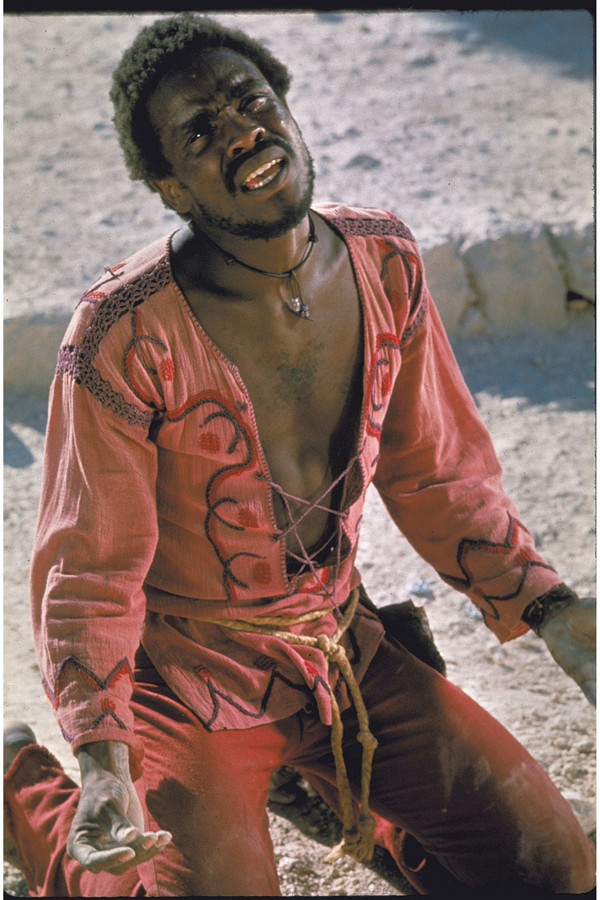

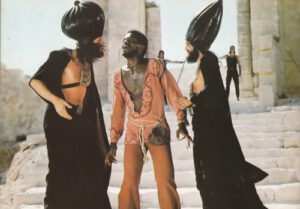

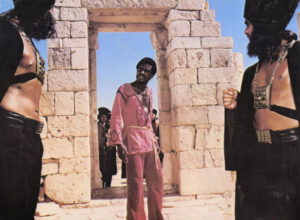

Judas Iscariot…………Carl Anderson

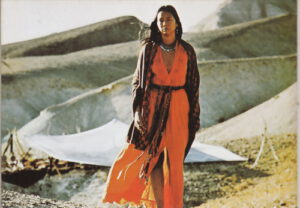

Mary Magdalene…………Yvonne Elliman

Pontius Pilate…………Barry Dennen

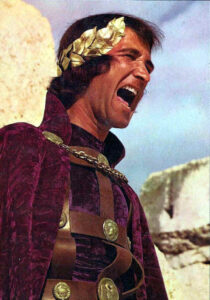

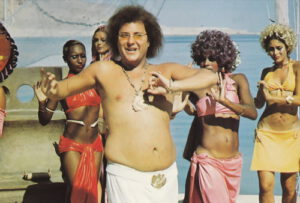

King Herod…………Joshua Mostel

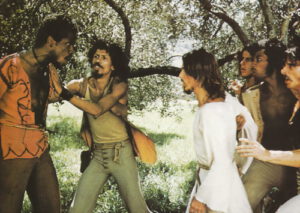

Simon Zealotes…………Larry T. Marshall

Caiaphas…………Bob Bingham

Annas…………Kurt Yaghjian

Priests…………Haim Bashi, Zvulun Cohen, David Duack, Avi Ben-Haim, Meir Israel, Amity Razi, David Rejwan, Itzhak Sidranski

Peter…………Philip Toubus

Apostles…………David Devir, Pi Douglass, Jeffrey Hyslop, Robert LuPone, Richard Molinare, Richard Orbach, Shooki Wagner, Thommie Walsh, Jonathan Wynne

Women…………Susan Allanson, Vera Biloshisky, Judith Daby, Leeyan Granger, Ellen Hoffman, Lea Kestin, Baayork Lee, Wendy Maltby, Marcia McBroom, Sally Neal, Riki Oren, Denise Pence, Adaya Pilo, Wyetta Turner, Kathryn Wright, Darcel Wynne, Tamar Zafria

Temple Guards…………Noam Cohen, Doron Gaash, Zvi Lehat, Moshe Uziel

Roman Soldiers…………David Barkan, Danny Basevitch, Steve Boockvor, Stephen Denenberg, Tom Guest, Didi Liekov, Peter Luria, Cliff Michaelevski

Orchestra

As noted below, a good deal of the “rock” or rhythm-oriented tracks were copied and pasted, in whole or part, from the original album; as for new material, André Previn led the 72-piece London Symphony Orchestra performing all of the arrangements and orchestrations of a more symphonic nature as a supplement, while the new rhythm tracks (as needed) were performed by a rock combo consisting, at various times, of the following musicians:

(Electric & Acoustic) Guitar: Ollie Halsall, Henry McCullough, Mike Morgan

Bass Guitar: John Fiddy, John Gustafson

Piano: Peter Robinson

Drums, Percussion: Bruce Rowland

Track Listing

French titles (from French dub, as recorded in Norman Jewison’s papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives) appear below in italic and parentheses.

Act 1:

Overture (Ouverture)

Heaven On Their Minds (Chanson De Judas)

What’s The Buzz (Qu’est-ce Que C’est)

Strange Thing, Mystifying (Cela Me Semble Très Étrange)

Then We Are Decided (Jerusalem Dimanche)

Everything’s Alright (Tout Ira Bien)

This Jesus Must Die (Jésus Doit Mourir)

Hosanna (Hosanna)

Simon Zealotes (Simon Le Zélateur)

Poor Jerusalem (Pauvre Jérusalem)

Pilate’s Dream (Le Rêve De Pilate)

The Temple (Le Temple)

I Don’t Know How To Love Him (Chanson De Marie-Madeleine)

Damned For All Time / Blood Money (Jusqu’a La Fin Des Temps / Je Ne Veux Pas De Votre Argent)

Act 2:

The Last Supper (Le Dernier Repas)

Gethsemane (I Only Want To Say) (Gethsemani)

The Arrest (L’Arrestation)

Peter’s Denial (Le Reniement De Pierre)

Pilate And Christ (Pilate Et Christ)

King Herod’s Song (Chanson D’Herode)

Could We Start Again Please? (Que Tout Recommence)

Judas’ Death (La Mort De Judas)

Trial Before Pilate (Le Proces)

Superstar (Superstar)

Crucifixion (Crucifixion)

John 19:41 (Jean L’Evangeliste: Psaume 19 – Verset 41)

Audio Production Information

Film Credits

Universal Pictures and Robert Stigwood present

A Norman Jewison Film

“Jesus Christ Superstar”

Starring

Ted Neeley · Carl Anderson · Yvonne Elliman · Barry Dennen

Screenplay by Melvyn Bragg and Norman Jewison

Based Upon the Rock Opera Jesus Christ Superstar · Book by Tim Rice

Orchestrations by Andrew Lloyd Webber

Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber · Lyrics by Tim Rice

Music Conducted by André Previn · Associate Producer: Patrick Palmer

Directed by Norman Jewison

Produced by Norman Jewison and Robert Stigwood

A Universal Picture · Technicolor® · Todd-AO 35

The French dub

Recent releases of the 1973 film on digital media — DVD, Blu-Ray, etc. — have included an alternate French dub. When it was released in France, the film came with this overlay, performed by the original 1972 French cast, including Daniel Beretta as Jesus, Farid Dali as Judas, and Anne-Marie David as Mary. Bob Bingham was also a member of the original French cast, and therefore is the only cast member in the film who dubs himself. (According to Jewison’s papers, Barry Dennen also recorded a Pilate vocal for the French dub, relying on dialect coaching and his memories of high school French, which was ultimately deemed unusable by the person supervising the dub. The whereabouts of Barry’s track are not known; likely it has either been lost or languishes in a Universal Studios vault.)

Daniel Beretta, who starred in the original French cast from 1972, sings “Gethsemane” in the French dub of the film.

Historical Notes from a Fan

When any show is a hit, a lot of people will be quick to capitalize on the show’s success. In this case, Jesus Christ Superstar was one of the first albums of its kind, and everyone wanted their slice of the pie where the Passion According to Tim and Andrew was concerned. As it often does, life imitated art, with all involved thrust unexpectedly into superstar status themselves, actually living (in a small way) the struggles Jesus deals with in the show. Tim Rice said in one interview, “It’s all a bit incredible. It has all gotten a bit out of hand — the orgy, the Superstar buttons and pocket calendars, the pickets, the T-shirts, the pirated concert versions touring around purporting to be the real Superstar…” And then there were all the potential official emanations to deal with resulting from the album and stage show, among them the film.

The seeds of JCS as a film were first planted shortly after the album came out in 1970. Yet to become a smash-hit, those involved had moved on to other jobs, among them Barry Dennen. His next job turned out to be playing the supporting role of Mendel, the Rabbi’s son, in the film version of Fiddler on the Roof, which was being shot in Yugoslavia by director Norman Jewison, who made his mark in the United States through fine television work and was most noted at the time for In the Heat of the Night, a crime drama set in a racially divided Southern town which starred Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger, and won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture (Jewison was nominated for Best Director). On set, Dennen and Jewison got along like a house on fire (the former would later tell JCS Zone “Norman Jewison was the most wonderful director to work with” and things ultimately went so well that, by the time he was part of JCS on screen, “I had done three pictures with Norman”), and Barry slipped Norman a copy of the record he’d just worked on, perhaps hoping industry attention would help the piece grow.

Jewison, in his autobiography, recounts that he immediately paid attention when he heard that “the BBC banned the British record album. They had found it offensive. Sacrilegious. I was intrigued…” Upon listening to the concept album, it struck a chord with the director. He felt it was a bit pretentious but that it was also marked with beautiful simplicity and sincerity. The fact that the record stood on its own without any spoken dialogue further impressed him. As he puts it in his autobiography, “I think I saw it as an opera almost the first time I heard it. I loved the idea, the music, and the lyrics. The scenes began to form in my mind before the first record had finished playing. […] The whole betrayal theme excited me and I was filled with all kinds of strong visual images.”

Bitten by the bug, he shared JCS with everyone he was working with. One such example was David Picker of United Artists, who visited Jewison’s London home while he was in town to see a rough cut of Fiddler. Says Jewison: “I played him ‘I Don’t Know How To Love Him’ and Herod’s song, and described how it would work visually, how each scene would develop, how the conflict between Jesus and Judas would drive the film. David looked at me like I was crazy. ‘But Norman, it’s just two phonograph records.’ He turned it down.” (This didn’t stop Jewison from talking up his ideas for JCS at Fiddler‘s New York premiere, however; he was quoted as saying at the time, “I could see it as an exciting innovative movie just as it was — just music and lyrics, no dialogue.”)

Meanwhile, brouhaha began to grow about the album, as it hit stores in New York, became an FM radio smash, and was, to quote Barry Dennen, “all over the place […] up and down Broadway.” Jewison told Dennen, “Your album is big,” which Barry, an early believer, was pleased to hear. He also let the actor in on his little secret: “I have an idea of doing it as a movie.” This being a day and age before cell phones, Jewison asked Dennen to introduce him to Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. And, as Barry nonchalantly put it, “so I did, and so they chatted.”

Jewison’s first impression of the authors was that Rice was “tall, burly, soft-spoken” and Webber “small, sharp-featured, angular, egotistic, so young he seemed still to be growing.” Whatever his thoughts of them, “[t]hey were both keen to work on the film version.” Queried about the controversy, “[t]hey weren’t worried about anyone accusing them of blasphemy; after all, they were using the New Testament for inspiration and this was just a rock opera based on the good, the bad, and the beautiful. In Tim Rice’s defense, he was more interested in the character of Judas than that of Jesus.” As for the authors’ point of view, he pleased them with his notion that there was only one place to film the rock opera — Israel — and was willing to allow them to work closely with him on all aspects of production (in one interview at the time, he even claimed Rice and Webber would “personally supervise every frame of the film”). Recalls Tim Rice, “Norman was great. He wanted us to be involved; we had lots of meetings with him, and I liked him a lot. […] I was asked to do a screenplay, and I thought, ‘Great! Fantastic!’ After all, the screenplay already existed, in that the lyrics were all there and the story was there, so really, it was a question of do I bring the Roman centurions in from the left or the right, or how many camels in this scene.”

The initial introduction having been made, “I called their agent in London, David Land. He answered his phone with the broadest of Cockney accents, surprised anyone would want to know who owned ‘that stuff.’ ‘It’s the boys, of course.’ […] ‘And who has the film and theatrical rights?’ ‘Decca, of course.’ I knew that Decca Records was owned by Universal. I sent a cable to Lew Wasserman and told him if he ever contemplated making a motion picture of Jesus Christ Superstar, I was his man. I don’t think he knew what I was talking about. But […] I had made enough of an impression on the major studios that Wasserman was pleased to hear from me. And so it began.” (Not without its bumps along the way; to keep the budget low, Jewison offered to work for no salary in exchange for gross participation. Dodging Wasserman’s cold stare, he argued that he was directing [and, ultimately, co-authoring the screenplay], and delivering them a finished film, and if Stigwood had a small piece of the worldwide gross, he wanted one, too, so he got one, and a producer credit to boot, in what he calls “one of the best deals I ever made in my life.”)

While Rice dreamed of a trouble-free screenwriting process and set about turning JCS into a film script, Jewison coped with the changes in the business structure that began to surround the piece: Robert Stigwood, the powerful and wealthy record impresario, bought out David Land’s agency, and with it the boys’ contracts. With the record now a big hit in America, Stigwood was contemplating a Broadway premiere, and since he happened to be a director nosing around the piece, Jewison was asked if “[he] was interested in staging it for the theater.” Wrapped up in his cinematic conception, Jewison told Stigwood he “really didn’t see it as a theater piece” but “would keep working on the film.” His opinion was affirmed when he attended the opening night of the Broadway production in 1971: “…rather too plastic, I fear, for my taste.”

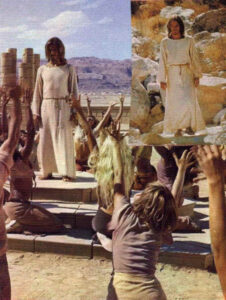

After seeing what Tom O’Horgan had done to their baby on Broadway, now that they were in a bargaining position, Rice and Webber were not going to allow Jewison to do to the film what O’Horgan had done to the stage version. Much to the relief of the public and the authors, Jewison stated, “Jesus Christ Superstar on the screen will not be anything like the Broadway production.” However, it would also not be quite what the authors themselves had envisioned. Jewison, who had been living with his vision of the film since before the album became a hit, had firm ideas about how it should be done, which he expressed to Cynthia Grenier of The Los Angeles Times in an interview at the time: “The one thing I knew for sure I didn’t want was a King of Kings job. I’ve seen Pasolini’s The Passion (sic) According to St. Matthew at least eight times; it’s so spare and simple and close to the Bible — and that’s what I had in the back of my mind.”

This was not what Tim Rice delivered: “I was asked to write the first draft screenplay. I set about this with great enthusiasm and minimum concern for budget, certain that a massive Ben-Hur kind of treatment was essential. Tens of thousands of extras would soon be thanking me for a boost to their incomes. After all, Superstar had not got where it had by excess subtlety or by its creators thinking small. All the words were already in place (though Andrew and I did expand one of the High Priests’ scenes in a futile bid to quash further anti-Semitism charges at the pass) so it was merely a question of pointing out which massive visual effect accompanied which song. Should the procession of camels enter from the left or right of the frame? What was the best marching formation for the Roman legions? These were the only kinds of problems I faced so within two weeks of being asked, I had submitted my script. Certain that I would not be required to do anything more, I sat back to await the invitation to Israel to see my extravagantly brilliant ideas transferred to celluloid. I was right in that I was not required to do anything more.”

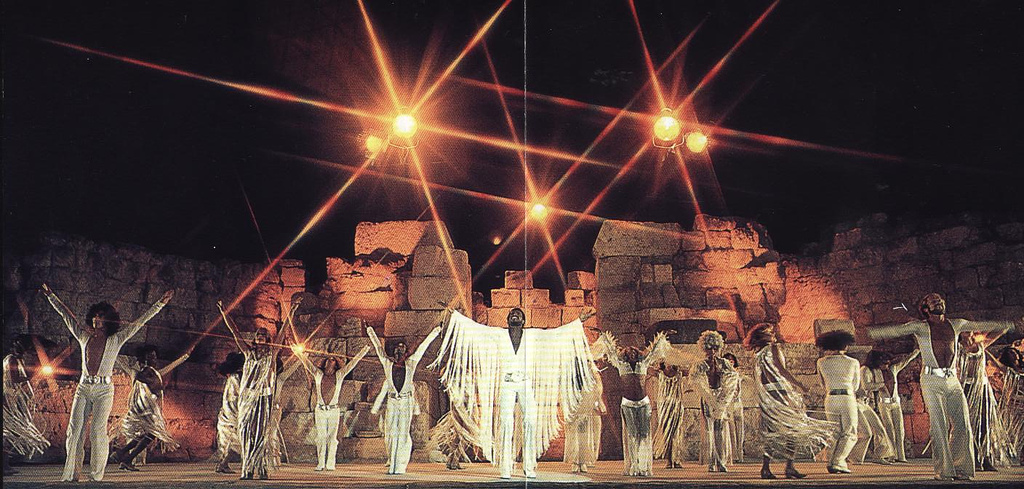

Jewison was taken aback and displeased by this elaborate and overlong treatment: “They had this very modern concept for the music but when it came to the visuals they lapsed right back to sheer Hollywood ’30s.” And so, although Tim Rice submitted a screenplay, it was ultimately Jewison’s interpretation (backed up by the studio, which made its decision after hearing his concept of an approach to the movie that called for, as Rice puts it, “a cast of dozens rather than thousands”) that made it to the screen. Says Jewison of his concept, “I hired a talented young British writer, Melvyn Bragg, to help me with the screenplay. […] in 1972 […] the two of us wandered all over Israel with tape recorders, listening to the music and lyrics and trying to figure out how the screenplay would work in a musical film with no text or book. […] When Melvyn and I finally decided that the film should be shot like a play within a play, we sat down and wrote out the action sequences that would fit with certain musical passages and would interpret the story using Tim Rice’s lyrics. We would open on an old Arab bus roaring across the Negev Desert, loaded down with props and costumes and, of course, our young cast of performers.” Recalls Tim, “I was not even asked to have a rethink; Melvyn was signed without my knowledge or consent and he, too, unencumbered by actually having to think up any plot or lyrics, delivered his screenplay in next to no time. […] I was fairly narked about this at the time…” (Ultimately, Rice would come around, saying in a later interview: “I had one or two worries about it at the time, only because it wasn’t how I’d imagined it, but looking back on it, I just see it’s a very interesting, original take by Norman Jewison and Melvyn Bragg, and we were incredibly lucky to get such an important director to make a beautiful film of our first major work.”) The film as Jewison envisioned it was ultimately budgeted at $3.5 million, which was just fine for Universal Pictures.

The next question was one about casting. Many Broadway actors and actresses had seen their roles go to Hollywood stars who, movie producers or studio magnates assumed, would guarantee stronger box office potential. (This is common practice for all movie musicals that studios consider financially “risky”; to quote one famous example, The Rocky Horror Picture Show was offered either a lavish budget with stars or a minimal budget with no-name talent and chose the latter, much to its eventual success.)

JCS was no different; a cursory glance at the section of Jewison’s papers (submitted to the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives) devoted to the film found an informal “celeb wish list” for Jesus that included such names as David Essex, Barry Gibb (a Stigwood client), Mick Jagger, Paul Jones (former lead singer for Manfred Mann), John Lennon (once rumored for the concept album), Paul McCartney, Robert Plant, and Leonard Whiting (most noteworthy at the time for his star turn in Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet). Also on the docket at one point or another were David Cassidy (then a newly-minted teen idol thanks to the success of The Partridge Family, later to essay the role in a stock production of JCS in a leaner time for many a Seventies celebrity known popularly as the Eighties), Alice Cooper, Micky Dolenz, and Bill Medley (of The Righteous Brothers; he would have no trouble reaching all those A-above-high-C notes in the Jesus songs). Sylvia Miles (then nominated for an Oscar for Midnight Cowboy) and Raquel Welch were both rumored to be top choices for Mary Magdalene. Other celebrities (and semi-celebrities) were clamoring to be a part of the film as well; among the more interesting submissions were Jim Backus (we came across a letter from him indicating he saw himself as a Judas or Herod type — Norman was kind enough to let him down gently), Leonard Frey (who had just worked with Norman in Fiddler on the Roof and indicated an interest in the role of Pilate), Helen Reddy (seen for Mary, likely off the strength of her success with “I Don’t Know How To Love Him” as a single), and B.J. Thomas (seen for the role of Judas at Stigwood’s request).

Norman had different ideas, initially intending to work largely with the cast of the concept album. For example, he had in mind Murray Head and Ian Gillan to reprise their roles. When Gillan was made the offer, it is reported, he didn’t get on with Jewison, he wasn’t all that interested in pursuing an acting career, and he wanted assurances the studio was unwilling to make — Deep Purple, now vastly more successful than they were at the time of the album’s recording in 1970, was about to undertake a world tour to promote their album Machine Head, and many of the dates conflicted with the film’s shooting schedule. Gillan was willing to restructure the tour around shooting, but in return, he wanted his bandmates to be reimbursed for lost profits from the canceled concerts. Universal, no doubt merely looking to turn a thin dime from what they felt could be a fad, said no, and Gillan returned the gesture, perfectly content to make more money on the road with Deep Purple. (Jewison subsequently turned his attention to Broadway lead Jeff Fenholt, who ultimately got as far as a screen test before being passed over for the final choice.)

As for Head, he’d been asked initially to reprise his role on Broadway but was unable to join the cast owing to issues with Actors’ Equity (Head is British), and at any rate, he’d become a successful screen actor, appearing in John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday, and consequently commanded an extremely high salary that Stigwood was unwilling to pay. For the film, he also got as far as a screen test before being passed over for the final choice.

Recalls Brian Keith, Annas on the original album: “I was offered the movie along with John Gustafson [Simon Zealotes on the album]. We flew out to meet with Norman Jewison, who was in his mid-20s at the time. He asked me if I’d had any acting experience, and I was too young to know that if they ask you if you can ride a horse, you say yes and then learn how to ride a horse, but I was too young and I was honest and told them I’d never acted before. Neither of us got called back.”

Ultimately, casting shook down to some of the authors’ choices (they favored, and got, Yvonne Elliman and Barry Dennen in the roles of Mary and Pilate once more), and a huge chunk of the Broadway company. Recalls Kurt Yaghjian, who won the role of Annas, “most of us were chosen from the Broadway show. Norman Jewison came out and picked the people he wanted from the show, like Ted [Neeley], Carl [Anderson], […] Bob Bingham [also a veteran of the original French company], me, Larry Marshall […] – just from the Broadway show.” The chorus was culled from Stigwood’s various tours of the show, and over 3,000 auditions conducted by Michael Shurtleff, with minimal input from Stigwood and Jewison.

Among those lining up for roles were many later screen stars and noteworthy names of the Broadway and West End stage; Timothy Bottoms and Christopher Walken were submitted for consideration for any part by their representation, and a grab-bag of Seventies and Eighties personalities including but not limited to Barry Bostwick, Northern Calloway, Irene Cara (later to briefly play Mary in a U.S. national tour with the film’s eventual stars in the early Nineties), Nell Carter, Jeff Conaway, Tim Curry, Clifton Davis (for Judas, at Stigwood’s request), Cliff DeYoung, and Marti Webb turned up for parts. Two audition stories from the film stick out in publicity: one of an actor hired, the other of an actor passed on. Joshua Mostel, son of renowned comic actor Zero Mostel, was cast as King Herod as a result of a reading he did for Shurtleff during casting for Pippin. His father, the original Broadway star of Fiddler on the Roof, was livid with Jewison for not casting him in the film version, and when he learned that Joshua had been offered a role in JCS, he is reported to have bellowed: “Tell him to go hire Topol’s son!” As for the other performer, one 17-year-old auditioned unsuccessfully for a part, but Stigwood kept him in mind for future productions. Three years later he would cast young John Travolta for the lead in the film that would make him a star: Saturday Night Fever.

When it came to Jesus and Judas, ultimately the hand of fate (and past casting practices) played a role. In the lead-up to the Broadway production, there had also been spirited discussions about casting the lead roles. In a 1993 interview, Ted Neeley reported, “I was brought into New York with essentially my choice to play whatever character I wanted, was basically what Tom [O’Horgan, with whom he had worked in Hair] said: ‘You’re in – just pick a part.’ So, I picked Judas. I go to New York all fired up, […] I sing the Judas songs, and Tom says, ‘Come here…’ [O’Horgan then broke the news that he was casting fellow Hair alumnus Ben Vereen as Judas.] And he said, ‘Can you come back tomorrow and let the producers hear you sing some Jesus stuff?’ And I come back the next day, and I [audition…] And he says, ‘Come here, we got to talk.’” At that point, O’Horgan informed Neeley that Stigwood wanted to use the stars of the concert version – Jeff Fenholt and Carl Anderson – in the Broadway show, while he preferred Vereen and Neeley. “I don’t know what the compromise is, so I’ll let you know,” he told Ted. Ultimately, as Neeley tells it in separate interviews, “As things turned out, Tom got his first choice on Judas instead. […] So he comes back and says: ‘How would you feel about being in the chorus?’” Neeley didn’t object (“I have a wide vocal range, so I understudied a lot of the male parts, including Jesus, and eventually got to play the title role”), and while Anderson was initially peeved (“We had a signed deal […] I lost out to Ben Vereen and went back out on the road with the concert company”), he ultimately got his shot on Broadway when Ben left the show with throat problems, and both were promised the leads in the Los Angeles production at the Universal Amphitheatre — and screen tests in London — as the trade-off.

Jewison was reportedly none too thrilled to have this situation dumped in his lap, but Barry Dennen urged him to check out Neeley (“a Southern rock and roller”) in particular; though Neeley missed the initial audition date during his spring ’72 run of Tommy, reports Jewison, he “later showed up at my hotel room. He tapped gently on the door and when I opened it, he was in full costume,” testament to his already strong dedication to the role. That summer, while attending casting and production meetings at Universal Studios, Jewison caught the L.A. production of JCS, which was winning over West Coast critics and audiences alike. Concerning Ted, Norman liked his “intensity, confidence, and wild falsetto wail,” but was initially against the casting – “I would have a very slight and small man for the role of Jesus.” He loved Carl’s work as well, but “was deeply concerned that the racial overtones of a black Judas would affect the whole film.”

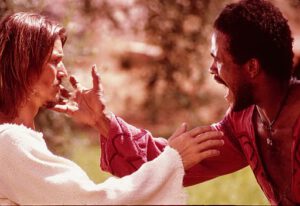

A meeting was called. Norman Jewison was frank about the situation when they arrived; as Neeley recalled in a Nineties interview, he said, “I got my Jesus and got my Judas. I don’t want to deal with a black Judas, and I don’t want to deal with recasting.” But since they had been promised the screen test, he was willing to fly them first-class to London and put them up in a nice hotel. Said Neeley: “We figured, ‘What the hell. We’re going to have a good time for a couple of days.’” Recalled Anderson, “So we took a couple of days off […] and were given first-class trips to London. All this, mind you, with the understanding that it was just a formality. We were promised the screen by the producer, and Norman was just accommodating Mr. Stigwood.”

Consequently, says Neeley, “[we] went into the screen test relaxed, figuring we didn’t have anything to lose.” At the screen test, hundreds of crew members applauded Neeley and Anderson’s performances of “Gethsemane” and “Heaven On Their Minds.” Although that might have been a clue, Neeley’s first was when “Norman asked us to perform additional scenes that hadn’t been originally scheduled.” Anderson recalled that Jewison asked them to do the confrontation from the Last Supper scene: “We had just rehearsed it in L.A., and it was on fire…” And so it was that a first in show business history was recorded: as previously stated, many a Broadway actor or actress had seen their roles go to Hollywood stars who, movie producers or studio magnates assumed, would guarantee stronger box office potential. This was the first time that the stars’ understudies got the plum. They played the Amphitheatre for less than two weeks, then left the show to go make the movie.

Pre-production began with the recording of the soundtrack, conducted by the legendary André Previn. (Says Tim Rice, “…as he made no effort to hide his basic loathing of the score (he went into print some years later describing Superstar as ‘shit,’ making one wonder how he could have so debased himself as to accept the job) we were unable to register much enthusiasm for his appointment.”) Ultimately, a good deal of the “rock” or rhythm-oriented tracks were derived, in whole or in part, from the original album, which featured musicians from Joe Cocker’s Grease Band, Screaming Lord Sutch, Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation, The Big Three, Juicy Lucy, The Merseybeats, Gracious, Plastic Penny, and Nucleus; as for new material, Previn led the London Symphony Orchestra performing all of the arrangements and orchestrations of a more symphonic nature as a supplement, while the new rhythm tracks (as needed) were performed by a rock combo incorporating three musicians featured on the original concept album. Recalls Kurt Yaghjian, “We went to London to do the soundtrack for the film because all the music was pre-recorded before we shot in the desert, and then afterward we went back to London to re-dub some of the takes that we couldn’t get the vocals to match with the recording — everyone had to redo some of it. But while we were there we got to hang out with Tim Rice, Liza Minnelli (who was real young at the time and had just gotten done with Cabaret), Ian Gillan, and Murray Head. They took us out to Pinewood Studios and we got to see Paul McCartney with Wings. It was amazing.”

Filming in Israel was less fun of an adjustment. Yaghjian again: “…we all got there two weeks in advance to get accustomed to the climate. […] I didn’t get sick, but a lot of the cast members did.” Barry Dennen was among those who didn’t adjust well: “It was very hot. Very. Uncomfortably hot. It’s desert – a lot of it.” To hear Dennen tell it, catering was also an issue: “I wasn’t happy about the food. Beautiful produce there, what they did to them… they’d take these wonderful carrots, sprinkle them with sugar, and serve them with raisins. They’d be served cold. Stuff like that. There was one day, or maybe it was a weekend, where they couldn’t cook, where they would deep fry eggs in oil, and let them sit and get cold for you to eat for breakfast the next morning. The food wasn’t that great. I understand Israeli food has come way up in standards since then, pretty much world-class. In those days it was not wonderful.” Though it was probably for a different reason, it is not shocking to learn from Yaghjian that “I fasted for the first week […] I spent the first whole week on just tea and fruit juice for the fast.”

Unfortunately for Barry, costumes were not without their drawbacks as well: “We all wore these ‘push ’em up’ boots to make us look taller. […] I had a pair of boots made for the picture and they were not made correctly. […] [They] were made like a pair of women’s high heels, in that the sole of my foot was on a 45-degree angle! Everything was pressing down on my toes. It made walking in those damn things very difficult, especially when trying to walk down the side of a mountain and all that stuff. Do you know that scene in ‘Pilate and Christ’ where he comes down the rocky stairwell? That wasn’t a stairway, that was just stone. You can see me take a step at one point. I was trying not to fall in them. The shoes were awful.”

But as time wore on during filming, camaraderie and joy at the opportunity they’d received suppressed any negative feelings. Recalls Dennen, “…making the movie was fun! We were all very, very excited to be associated with it. […] We were all very happy to be working together. Most of us were from Broadway. […] Ted, Carl, Yvonne, and the rest of the cast were simply the best. […] It was a wonderful experience. I loved it.” As Yaghjian put it, “It was spectacular, and we were all so moved by being in the Holy Lands. […] I was very moved. Lots of people there felt spiritually moved.” Small wonder, considering the locale; Kurt recalls that “Then We Are Decided,” the new song in which the troubles and fears of Annas and Caiaphas regarding Jesus were better developed, was shot “on the top of Herodium, which was Herod’s lavish retreat.” Production took them all over Israel. “We were also in Jerusalem and Beersheba as well. The scene with the priests on the scaffolding was done in Beersheba. We had to wake up early to get there at dawn, but I loved it.” Dennen recalls the morning drive fondly: “…we had to get into one of those mini-buses and take an hour drive out to the location for shooting in the desert. Every day, we played the George Harrison album All Things Must Pass on the car stereo. It seemed to me to fit the mood of the show.”

The shoot was not without its strange moments as well. In reminiscing, Yaghjian refers to one such incident: “The crucifixion scene was really scary. We were in the middle of the desert, and while we were setting up, these dark clouds came out of nowhere, and this cold wind started blowing hard. Just as Ted got up on the cross, at the horizon, there was this little sliver of light that started to lift and the sun started to come through. I get chills thinking about it – it was really scary.”

The ultimate test of any film is how it is received, by both critics and audiences. Unfortunately, at the time and immediately thereafter, the film did not meet with warm critical reception. As Jim Lane puts it on his blog Cinedrome, “It was as if critics all over, embarrassed at the hyperbolic praise heaped on the album two years earlier, when it was compared to Bach and Handel, had decided in some secret meeting to take it out on Jewison’s movie. […] Even when a review was positive […] it carried a snide, patronizing air of I-can’t-believe-I’m-expected-to-take-this-thing-seriously.” In Newsweek, Paul D. Zimmerman blasted the film, calling it “…one of the true fiascos of modern cinema… Lord, forgive them. They knew not what they were doing,” and observing that Neeley’s “Jesus often recalls Charles Manson.” Bruce Williamson of Playboy enthusiastically declared that Neeley’s “portrayal of Christ ought to fix him permanently in public memory as the Screamin’ Jesus.” In 1980, film critics Harry and Michael Medved would “honor” Neeley in their book The Golden Turkey Awards with “Worst Performance by an Actor as Jesus Christ.”

Jewison was forced to defend his vision of the picture before its release in a Playboy interview: “We could have been vulgar. We could have played this for cheap. Nothing simpler. Guaranteed socko at the box office. We could have been filthy. But we weren’t. For instance… half the apostles are gay, right, and what about Jesus and Judas? …A big, wet smackeroo, right on the lips. How about that? Oh yeah, we could have been vulgar all right. We could have milked it for every grab in the book. But we didn’t. Instead, we decided to make it beautiful… We made it into a spiritual experience and it’s beautiful, and Jesus is beautiful, the kids are beautiful, it’s going to be a beautiful film. People are going to see it in drive-ins and neighborhood nowhere theaters and they’re going to be moved by it. People who were never moved by this story before. People who always thought that Jesus Christ was some kind of a schmuck. They’re going to see something beautiful and they’re going to cry. They won’t be able to help themselves. When you come to think of it, we’re doing Him a favor.”

Jewison’s assurances to the public aside, even the authors were not particularly thrilled. Recalls Tim Rice of their (non-)involvement in his autobiography, “Andrew and I took a total back seat. […] David Land, Andrew, and I went out for just three days to have a look at things, and we continued to exert no influence on proceedings, spending most of our time sightseeing in Jerusalem, Jericho, and the Dead Sea. […] My principal memories of our visit to the filming were hilarious van trips around Israel with David Land in top form, regaling us with his wartime experiences (‘first man away at Dunkirk’) and less than politically correct views about the Arab-Israeli situation, often delivered astride a camel. Yvonne and her husband Bill Oakes were almost the only people involved with the picture that we spoke to and they joined us for my twenty-eighth birthday celebrations at a Jericho tavern with an unusual menu. We remember the joint to this day as the Angus Snake House.” (More charitably, he would later opine, in an interview for a Special Edition DVD release of the film, “I think there comes a point when you know when it’s not right to interfere. There wasn’t much we could do. Norman and his team had got their way of doing it, it was working well; for us to come in and say, ‘Look, can you make Mary sing this line here?’ …that would not have been a good move. There was nothing we could have done that would have materially affected their vision, and nothing we really wanted to do.”)

His views of the final product, however, remain mixed at best: “The film was eventually released with reasonable fanfare in the summer of 1973, barely a year after the début of the West End stage show (still going more than strong). It was neither a huge success nor a complete flop. […] The choreography was by Pan’s People out of Hair, the costumes were mid-period Who, and despite some beautifully photographed sequences and one or two fine performances, for the first time in its meteoric streak across the showbiz heavens, Superstar seemed out of touch and out of fashion.” For his part, Andrew Lloyd Webber was less subdued in his viewpoint in a recent interview promoting his arena tour of the show: “I hate the film. I can see what Norman Jewison was trying to do, but I could never look at it. I don’t see how you could do that show as a film anyway.” (However, only a few years later, he had softened, phrasing his remarks in a Times Talks conversation as follows: at the time, he wasn’t sure about it — he thought it might date — but “the curious thing about it now is, it’s held up much better than I ever thought.” He went on to clarify that the sound in cinemas was very poor quality at the time, and he recalled attending a screening in Chicago and hearing it in mono, much to his chagrin. Says he, “It would be interesting to hear what Superstar would sound like if the soundtrack was remixed, and they could easily take that and remix it again.”)

However, whatever its reception may have been, much like the Broadway production before it, it was a financial success. Coming a mere three years after the musical was born, the first film of JCS grossed $13.2 million at the box office (turning a more-than-respectable profit on Universal’s initial investment), earned North American rentals of $10.8 million, was nominated for two Oscars and six Golden Globes and won a BAFTA. Years later, the film is still popular; as recently as 2012, it won a Huffington Post competition for “Best Jesus Movie.” Since its 40th anniversary a year later, a North American tour of screenings of a digitally remastered print of the film, incorporating in-person appearances by its stars, talkbacks with the audience, and now a singalong and costume contest, has met with resounding success and currently plans to continue its run until interest wanes. And the stars of the original film have reunited onstage, sometimes to massive financial returns, at various times in the show’s history.

For many of the show’s fans, the film is the benchmark — a reference point, a coordinate system, alpha and omega — by which all versions of JCS are judged. One would be hard-pressed to ignore its impact. Subsequent directors and producers have tried to make their versions “fresher,” more up-to-date; sometimes the treatment will be interesting to look at, and critics will often praise it as a successful experiment. Fans will nitpick over which element was the most successful, how smart the director was to cast this or that performer or praise something different in the musical arrangement, and finally, conclude that JCS never changed all that much anyway. But ultimately, in the eyes of many fans, there’s no beating the original — such attempts at an update pale in comparison to the 1973 film, which comes closest to the mark. Despite the dated hippie costumes of the ensemble, the characters are realistic, relatable, and recognizable; the musical direction is strong, more or less retaining Webber’s original orchestrations (though at times the orchestra is even more nuanced than the original album), and the vocals are rarely less than terrific, save for the odd moments when the chorus singing sounds a bit wayward (and soprano-heavy); and the natural scenery of Israel lends additional plausibility to the film. The future still lies ahead, and it remains to be seen whether a new remake may yet topple the almost fifty-year-old chestnut, but in the meantime, look, listen, and enjoy. This film still works remarkably well.

Reviews

Jesus Christ Superstar still amazing fifty years later

This Movie was a big hit here in Australia it had a three year run at cinemas all over the country. I had the pleasure to see this movie in April 1977 with my grandmother a movie i give it five stars because it deserves it.

What???

If not for Carl Anderson, this would be a one star review. The audio is of much lower quality than that of the original album, and the timing on the vocals is almost always off, especially in King Herod’s Song and This Jesus Must Die.

I grew up to this version and it's superb

After seeing the film as a young child, I listened to the original album but the film soundtrack was imprinted in my mind. I bought the film track CDs in the 90s but the quality is terrible. Just like ALW, I’m dying to hear a faithful, remixed film CD set! It seems we’ve got a Disneyland / Disney World thing going on where the original is (justly) revered but the newer version needs its due!!

Oh my lord

Being in Australia I grew up with the ‘92 cast recording that my parents and sister played on repeat. I didn’t see the film until much later when the national broadcaster (ironically or not) played it on Good Friday, and with nothing else on TV I watched it.

I was blown away. Particularly by Carl Anderson and Barry Dennen. I wasn’t all that convinced by Ted Neeley until Gethsemane, but that changed my mind. The way these three performers portray being caught up in events where they must play their part and do terrible things without having any control, but do them anyway… it gets me every time. “Everything is fixed, and you can’t change it.”

The quote from Norman Jewison above:

“People are going to see it in drive-ins and neighborhood nowhere theaters and they’re going to be moved by it. People who were never moved by this story before. People who always thought that Jesus Christ was some kind of a schmuck. They’re going to see something beautiful and they’re going to cry. They won’t be able to help themselves.”

That’s exactly what effect it had on me. Not having a religious upbringing I’d not known the story well, and I’ve since learned that Judas’s motivations depicted in the film are a somewhat radical interpretation of the Bible, but it’s the version that works for me.

After finding this site I’m keen to track down and listen to some other versions, but I think this one will be hard to top.

My first Superstar experience

The original motion picture soundtrack will always have a special place in my heart. I saw the movie before I heard the concept album. This movie was my first ever Superstar experience and it has therefor earned that special place. The cast is also my all time favorite. For me the name Jesus is almost synonymous with the name Ted Neeley. This man has inspired my fandom for this great rock opera and send me on the path to collect as much material as I could find on Superstar and to keep the legacy alive as best as I could. Carl Anderson is most likely the second reason, I love this man’s voice! It broke my heart when I heard he died from leukemia at age 59. The world truly lost a great talent that day. Yvonne Elliman will always be the Mary Magdalene that I’ll try to compare every other Mary too, even if it’s not the right thing to do. Lastly Barry Dennen gives perhaps one of his finest performances here. If you’ve never listened to any JCS cast album this wouldn’t be a bad place to start.