All rights belong to their respective authors. If you wish to use this material, please contact us.

Interview conducted by Gibson DelGiudice.

Photographs courtesy of Special Collections/Musselman Library, Gettysburg College.

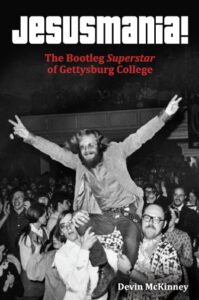

Unlike most other JCS Zone interviews, which have been mainly with performers who have appeared in various productions of the show, this interview is with Devin McKinney (pictured right), a published author on pop culture and archivist at Gettysburg College. Last year, he wrote Jesusmania!, a new book about a wildly successful (and illegal) amateur production presented at Gettysburg in the spring of 1971, which you can read by clicking here (at the time of this interview’s initial publication, the hard copy was available in a limited print run of 500 copies, signed and numbered by the author; if you prefer something you can hold in your hand, a small number of print copies are still available by writing to Musselman Library, Gettysburg College, 300 N. Washington St., Gettysburg, PA 17325). As not much is otherwise recorded about the early days of unauthorized productions, JCS Zone decided to get the scoop on this historical account. The results follow.

Q: Hello, Mr. McKinney. Thanks for consenting to an interview! For starters, please tell us a bit about yourself and the other work you’ve done.

A: Thank you for the invitation. I’m mostly a critic but I also consider myself an untrained, unlettered cultural historian. As well as Jesusmania!, I’ve written books about The Beatles (Magic Circles, 2003) and Henry Fonda (The Man Who Saw a Ghost, 2012), and each is about the interaction of creative individuals with social and historical forces, resulting in cultural moments that I think have lasting value and meaning. My shorter writings — reviews, essays, fragments — have tended to go along the same lines.

Q: Before we continue, I’d just like to tell you I read the book cover to cover in one sitting, and I loved it. I must say, I was pleasantly surprised; I didn’t understand exactly how someone could devote 302 pages to this, let alone wring a book of any substantial length out of a single production, but it proved as fascinating and in-depth as everything I had read about the book promised. With the heaping helping of sociological context you gave, I felt Jesusmania! captured not only the production, but the people and the times it came out of, to the degree that I felt like I was there watching them put it together. I couldn’t help catching their excitement.

A: Wow. I know you’re a devoted fan, but that you ingested the book in a single reading impresses, and flatters, me. Thank you for the kind words. I certainly wish I’d known about Jesus Christ Superstar Zone! You would have been a good resource.

Q: I can only say — flattery never being out of style — that surely a reader’s inability to put a book down is the mark of its author’s considerable skill. Let’s begin. How familiar were you with Superstar before embarking on this endeavor?

A: I was a child of the Seventies, so it was part of the background. Murray Head’s “Superstar” and Helen Reddy’s “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” were heard a fair amount, and on the schoolyard, we sang an irreverent version of the “Superstar” refrain. Getting older, and becoming a dedicated rock fan, I scorned Superstar because it wasn’t rock, it was Broadway — though I always loved Yvonne Elliman’s version of the Mary song. That was the extent of my knowledge or interest before I began researching Jesusmania!. After this, I got to know the work very well and respect what it does and what it is.

Q: …I’m sorry, I’m still trying to wrap my head around this. Does this mean you never saw the film(s) or any stage production(s)?

A: I never saw or sought to see Superstar on stage or screen. By chance, the community theater here in Gettysburg staged it just a few months after I’d begun researching the book. It was just fine, by community theater standards. That was the first time I viewed it in any form.

Q: I see. Would you say that your… how do I put this… essentially blowing Superstar off was due to being a rock “purist”?

A: Although for a long time, I didn’t consider Superstar quite “legitimate” as rock music, I never considered myself a purist, i.e., a rockist. I simply knew that “rock musicals” (JCS, Hair, Grease) tended to be written by people whose tradition was not Elvis or Chuck Berry or even The Beatles, but Rodgers and Hammerstein. To me that’s not a value judgment (Rodgers and Hammerstein can break my heart), it simply recognizes a difference in orientation that you can hear in the grain of the music. I still love the record of Hair in its first, Off-Broadway, Public Theater incarnation, but it’s not rock, pop, raga, or soul — it’s a pastiche of those styles. No one would mistake “Hair” for The Rolling Stones, “Manchester England” for The Kinks, “Walking in Space” for Jefferson Airplane, or “White Boys/Black Boys” for The Supremes.

Q: Fair point. Let’s move to the subject of your book. How did you first discover the existence of this Gettysburg College production?

Q: Fair point. Let’s move to the subject of your book. How did you first discover the existence of this Gettysburg College production?

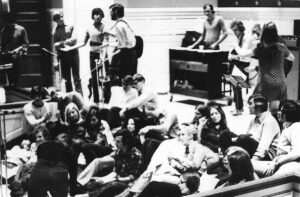

A: I work in the archives of the college library, where everything relating to the school’s history is kept. I found a folder marked “Jesus Christ Superstar — 1971,” and looked inside. There were rehearsal schedules, and other documents suggesting this production had been carried out in defiance of a court order. There were photographs, of students wearing great 1971 hair and clothes. There was even an audio recording of a performance. All the material was there to get me started. Then I thought, why not see if some of the people who created this were still around and willing to talk about what they remembered?

Q: What made you decide to write a book about it? Did you consider doing anything else with the material?

A: At first I thought I’d do a modest audio-visual presentation, or maybe a paper for an archivist’s publication. But as I got deeper in, did a few interviews, and discovered how much this event had meant to people, it felt like a book. It had a large and interesting cast of characters. It had the intersection of creativity and history that I like. It was set in a period I already knew pretty well, and it had pop music and some kind of legal drama behind it. It was a type of project — detailed, reconstructive history, based on a lot of interviews and archival research, revolving around a musical work that was strange to me — that I’d never done before, so it would be a new, fun challenge, full of discoveries. There was nothing about it that didn’t appeal to me.

Q: Your press material for the book describes the production as being “mounted by a handful of students, a few faculty members, and a seminarian.” While I’m sure the idea of staging it caught on like wildfire, as it did with many churches and schools across the country, whose initial idea was it to stage the show and why?

A: The seminarian, whose name was Larry Recla, was very much the driver of the show, its overseer and energy force. But I believe the idea came to him from a student named Clay Sutton. Clay was a biology major and member of Gettysburg’s Class of 1971. He remembered very clearly buying the Superstar album in a record store across the street from the off-campus movie theater, taking it to the campus chapel, and introducing Larry to it. I surmised from my interviews that it began with the two of them simply sitting in a basement room, getting turned on by the music, and imagining the possibilities of a live performance. This would have been mid-December 1970, not long before the Christmas break.

Q: In your research reflections, published in the Friends of Musselman Library Newsletter, you say that “performance rights, first granted, had been abruptly withdrawn, making the enterprise illegal.” Can you elaborate on this point? Who granted the rights?

A: Larry Recla sought and received performance clearance through the New York office of MCA Music, which owned the publishing rights to the compositions. A fee had even been agreed upon. But what MCA apparently didn’t know was that Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice had already signed a contract giving Robert Stigwood, the pop promoter, a five-year exclusive on all stage and screen versions of Superstar. Stigwood was planning a huge Broadway debut, and once he became aware that all these amateur groups were performing or planning to perform the work, he obtained a court injunction to stop them. That made it illegal for anyone to perform Superstar without permission from the Stigwood organization, and the Stigwood organization wasn’t giving permission. At which point, MCA was forced to write to Larry Recla, and everyone else they’d granted rights to, and tell them, essentially, “Sorry, we were wrong.” Larry and his students were about to begin rehearsals, and now they were faced with the choice of obeying the injunction or forging ahead. They chose to forge ahead.

Q: It’s interesting to hear you say that, because according to Tim Rice’s autobiography, in order to record the very first trial single (the title track), the authors were forced to accept a deal granting MCA “rights to participation in every subsequent aspect of the project,” but Tim mentions that Andrew insisted the grand rights (“in effect the theatrical presentation right to the score as a show”) be specifically excluded from the deal. To the extent that what Tim says is true, MCA didn’t have clearance to issue such rights, to begin with, regardless of Stigwood’s involvement.

A: I was piecing the narrative together from Gettysburg correspondence, Lloyd Webber biographies, legal briefs available online, and contemporary reports in the popular press (mainly Billboard). The version I got is that Superstar Ventures Ltd. was formed in October or December 1970, at Stigwood’s behest, with himself and ALW and Rice as partners and that this was specifically to oversee all stage and screen versions to come. I hadn’t read Rice’s book, or anything else suggesting it was ALW, as opposed to Stigwood, who had the foresight to separate “grand rights” from publishing rights. That nuance, if accurate, is something I missed.

Q: Well, this point did have to be established — several times — in a court of law before legal precedent (that is now a case study in many entertainment law textbooks, incidentally) was set in the summer of 1971, so it is clear confusion was ruling the day.

A: (In agreement) Whoever reserved performance rights and when, MCA clearly assumed it had the power to grant them, simply because no one had told them they didn’t. Until Stigwood took it to court.

Q: In your research reflections, you say that you had discovered “the production involved students from all classes, majors and campus subcultures (with a few professors and non-collegians thrown in).” Leaving aside obvious causes (i.e., the popularity of the album, the growth of the Jesus Movement nationwide, etc.), did anyone surprise you with their story of how and why they got involved?

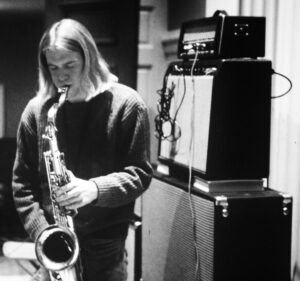

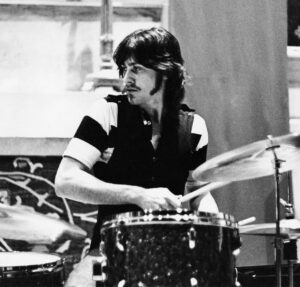

A: None of the stories was really a surprise, once I knew a bit about the individuals, but each one was interesting because it illustrated in some way the person’s character or conflicts. Some students were in spiritual or emotional turmoil, and for them, the show became a way of expressing or overcoming that. The dancers simply enjoyed getting a chance to do their thing. Others were interested only in the musical complexities. The organist wasn’t even a student — he was an experienced rock player from a neighboring town, and the only person around with a Hammond organ who could play music by ear, without a score. The drummer wasn’t from Gettysburg, either, but a professional who’d been in rock and jazz bands, and backed up the great blues guitarist Albert King on American and English tours. See what I mean? The more I learned about the people involved, the more interesting the story got.

A: The cast was mostly assembled by word of mouth — people being matched to roles that seemed to suit them — but there were also auditions for certain parts. I think Mary was particularly vied for since it’s the only strong female role. The singers were all over the map in terms of previous experience. Some had performed in musicals in high school; some had seen them on Broadway, but never been in one themselves; some hadn’t done either. Of the four faculty members who played the high priests, three had sung in church choirs, but the other didn’t even sing in the shower. Jesus was a former student who years earlier had co-founded a jazz vocal group that was highly popular in the mid-Atlantic region. The students who played Mary and Herod were highly trained singers accustomed to public performance, but not of this kind. So almost all of them had musical experience, but it was divergent, and not quite like what Superstar would require of them. Several members of the chorus, on the other hand, were not trained at all, and their performance experience was limited to singing with friends in their dorm rooms.

A: Larry Recla had the luck to see the Royal Shakespeare Company production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Peter Brook, at the Billy Rose Theater in very early 1971. His Superstar was already well into the planning. The RSC production was minimal in costuming and props, and almost void of scenery, and it inspired him to go for clarity and simplicity. Since the show would be in the chapel, not the ballroom where official theatrical productions took place, there was already relatively little they could do with scenery or stagecraft. Ultimately there was some dramatic spotlighting, but not much, one or two props, and a Superstar banner overhanging the stage. As for costuming, Larry wanted a contemporary, not a historical, feel, so everyone wore their ordinary street clothes. That was except for Judas, who was all in black; the high priests, who wore academic robes (an ironic comment on the faculty as “establishment” figures); and Herod, who wore an American flag bathrobe and a necktie covered with Budweiser logos.

Q: How interesting! (Actually, quite refreshing in Herod’s case; most directors, taking their cue from the original Broadway production, inexplicably make him comic relief in the form of a gay stereotype.) It is our understanding, from your answers here and your book, that only an audio recording survives, so there is no clue what effect performances may have had visually other than from still photographs. Given this was a very simplistic presentation, is there any indication as to whether the evening was primarily sung with choreographic interludes, or whether there was some staging, acting, etc.? Did anyone furnish helpful information to that end in interviews?

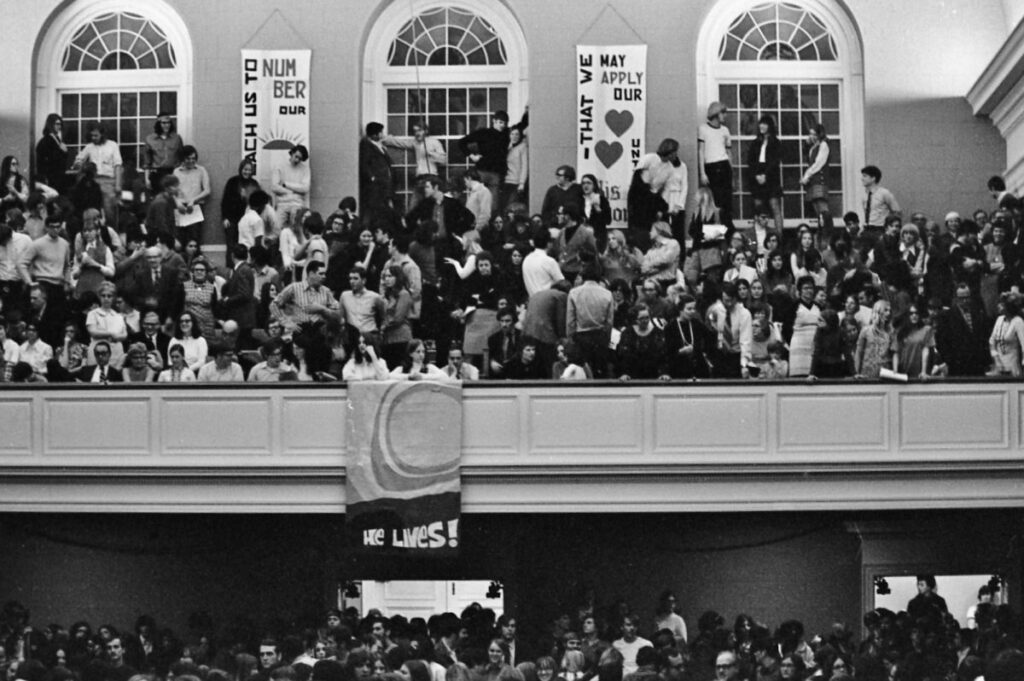

A: I depended entirely on interviews for that information. The rare bits of “acting” business, such as Caiaphas tossing a bag of silver to Judas, were recalled by the actors involved if no one else. Others had strong memories of the choreographed dance that accompanied “Hosanna.” The performance program listed dance solos during the “Damned for All Time” and “39 Lashes” numbers, and I spoke to the dancers about how they’d moved, and what they’d tried to communicate. Some people remembered facial expressions or physical attitudes struck at specific points. And everyone recalled the euphoria of the finale, with the performers proceeding from the stage into the audience, with Jesus on the shoulders of Pilate and Herod. (Interviewer/editor’s note: This is the moment depicted on the book’s cover above.) I wanted to give the reader a strong sense of the performance as an immediate event, so I asked everyone for their visual impressions and memories of specific movements or moments. 1971 was long ago, so people were often understandably vague, recalling only a general sense of overwhelming excitement. But enough specifics accumulated that I could recreate the performance from beginning to end in fair detail, considering the absence of video evidence. (The photographs, of which dozens were taken, were of great help in imagining the staging.) While I was writing, someone threw me the word “oratorio.” I’d heard it without really knowing its meaning, and I realized that this staging had followed the same principles. It had some acting, some dancing, some props, and a lot of motion, but it wasn’t a full-fledged dramatic rendering. Mostly it was a straight-on performance of songs sequenced to tell a story.

Q: You mentioned above that the performance took place in the chapel as opposed to the ballroom usually used for theatrical events. Did they do this at the chapel because the project originated with Larry, or because the university was unwilling to let its main space be used for a production of questionable legality?

A: The chapel was used simply because the project originated there. It was never under the auspices of the theater or music programs; it was always strictly a chapel thing (e.g., funding was through the Chapel Council and the Central Pennsylvania Synod, the regional ruling body of the Lutheran Church).

A: The student who portrayed Judas admits he was in over his head with the part. The faculty who played the priests were even more so. Not everyone in the show was steeped in vocal training. But one thing I love about the Gettysburg Superstar is that it’s raw, passionate, and imperfect, full of people fighting the limits of their technique to express themselves, sometimes but not always breaking those limits. Zane Brandenburg (Jesus)’s screams on “Gethsemane” are something to hear. As for your question… this aspect is dealt with at length in the book. Cutting the crucifixion was a very deliberate choice on Larry Recla’s part. Quite simply, he wanted the show, unlike the album, to end on a high note rather than a low, with a triumphant, resurrected Christ rather than a defeated, crucified one. Secondary and tertiary considerations were that the closing numbers on the album, “The Crucifixion” and “John 19:41,” simply didn’t lend themselves to being played by a rock band with horns; and that removing the numbers tightened up the running time.

A: I asked Larry about that, and his reasons for cutting those songs were not so specific. But he implied that they slowed the narrative he wanted to shape. His reconfiguration of the libretto makes it clear that he was not chiefly concerned with driving home the biblical references, or even with replicating the standard Holy Week narrative. He wanted a lean and mean drama, a relentlessly building intensity ending in an ecstatic climax. I’m sure he thought these two songs detracted from that more than they added to it.

Q: It’s a fair cop. Well… I feel I would be remiss to my readers at JCS Zone if I didn’t try to press the point one last time. You say you weren’t a fan of Superstar when you began. Were you a fan by the time you finished?

A: I wouldn’t say I’m a fan of Jesus Christ Superstar, in that I want to hear every production I can find. But I became a passionate fan of the Gettysburg Superstar. I developed a strong emotional connection to it, but I also think it’s a magnificent rendering on its own terms. Not perfect or highly polished, but very loud and alive and (to use a word often repeated by people who saw it) electric. I prefer it to the original album, which is a bit sterile in comparison; and, except for Carl Anderson’s Judas, I think it blows away the movie soundtrack. Beyond that, I don’t really need to go. Being a Beatles fan, for instance, doesn’t mean seeking out, let alone loving, every version ever done of one of their songs. For me, Gettysburg is the “Beatles” of Jesus Christ Superstar, the pinnacle and definition of what that music can be.

Q: Well, that’s bound to be contentious for our readers, but it’s certainly an interesting point of view. I think it’s about time to wrap this up, so I’ll close with this question: what do you want readers of this book to take away from the experience upon having read it?

A: I’d like a reader to come away thinking, “That was a lot more compelling than I thought it would be,” because that’s the experience I had writing it. Except for the historical period and the presence of rock music, there was nothing there that I had an existing hold on. I wasn’t a Superstar fan; I was fairly new to Gettysburg College; I didn’t know anyone involved in the production; and I’m an atheist. I knew that this project would require me to care less about what I liked or felt natural with than to understand what other people liked and felt natural with. But that came easily because the story, as I’ve said, kept getting more interesting. I never forgot that it was a little story, a little splash at a little college created by a little group. But I think most of history is little stories forming the mosaics that become big stories. I want readers to come away feeling that they’ve seen the historical and human implications in what they might have thought was at best a pleasant anecdote about something that happened in the middle of nowhere almost a half-century ago.

Q: Thanks for a terrific interview!

A: Thanks again for the opportunity to enthuse and expound. I hope your readers find it of interest.